Queer Nature: Anthropological Reflections from my Summer at Kew Gardens

By Mahliqa Ali

‘Isn’t this wokeness gone mad, first plants are racist, and now you’re saying plants are gay?’

During the summer of last year, I worked at Kew Gardens, and when I heard that we were hosting an event called ‘Queer Nature,’ this was exactly the kind of comment I expected to hear. Based in Richmond in Surrey, the typical Kew Gardens visitor is reflective of the typical inhabitant of this scenic West London borough; most members and regular visitors are white, middle-class, middle-aged locals, and the area is known for its high number of Tories; unsurprisingly, Richmond Park & North Kingston Conservatives have one of the largest memberships of any Conservative Association in the UK.

The day-long 9am-5pm training session held for the Visitor Hosts reflected my fears – we all anticipated a backlash from the average Kew clientele, who might voice similar critiques to right-wing media personalities such as Piers Morgan, who ranted about ‘Kew going woke,’ and angrily questioning ‘Why can’t we just have straight plants?’. From these preliminary responses, Kew management developed a training programme in collaboration with an EDI session facilitator for us to prepare responses to homophobic comments we may receive from Kew-goers who were offended by placards stating that fungal reproduction is often asexual, and that many palm trees have both ‘male’ and ‘female’ reproductive organs.

The training sheet involved scripted answers to the questions, ‘Isn’t this jumping on a woke bandwagon, what do plants have to do with people being labelled queer?’, ‘Why is Kew running a festival just for the LGBTQ+ community?’, and my personal favourite, ‘Isn’t this wokeness gone mad, first plants are racist and now you’re saying plants are gay?’

The standard of the training impressed me – they covered common LGBTQ terms, defined labels, covered the history of gay rights and the sensitive history of the word ‘queer’ itself, prepared us to give answers which would shut down blatant bigotry and minimise complaints, and took the time to teach us about the individual contributing artists and their work.

The exhibition involved several installations within the Temperate Greenhouse, in the form of spoken word poetry, tapestries, plant installations, videos, and information boards, all along the theme of demonstrating that nature evidently does not fit into male/female binaries of reproductive parts and processes, and despite scientific aims to categorise plants and their characteristics into bounded classifications, the diversity of nature is not best portrayed by these rigid systems, just as humans are not. The After-Hours events involved music, cabaret, comedy, and drag performances.

The combination of the heavy preparation we were doing in anticipation of negative feedback from the event, and what we were hearing about general attitudes from the loudest voices in right-wing media (and the comments on Richmond community Facebook forums), myself and the other Visitor Hosts felt a lot of apprehension for the exhibition. I was almost certain that it wasn’t going to be well received, that we’d have to deal with homophobia every day, and that it would be a disappointment to queer people who would find it overhyped after they travelled to see it because of the adverts all over London.

But when I walked into the Temperate Greenhouse for my first shift at the exhibition, I was very pleasantly surprised to find Judith Butler’s face on a huge poster looking back at me. The entire exhibition had been so thoughtfully curated; it was a genuinely beautiful collection of art, science, and gender theory.

House of Spirits - Jeffrey Gibson

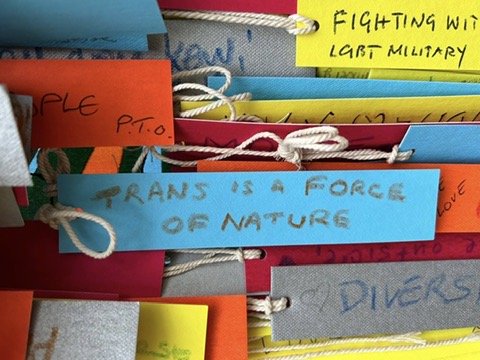

There was a spoken word poetry performance called ‘Reverberations’ by two artists about diversity, beauty, and queerness in nature, a planted area of pansies in honour of ‘The Pansy Project,’ in which artist Paul Harfleet plants pansies at sites where homophobic and transphobic violence has occurred across London and the world, a plant display called ‘Breaking the Binary,’ curated by Patrick Featherstone Gardens, comprised of plants which reproduce in ways that challenge conventional norms of male/female binary reproduction, a tapestry titled ‘House of Spirits’ by Jeffrey Gibson, created with botanical illustrations from Kew’s archives as an homage to the underground ball subculture of queer African-American and Latino communities in New York City, and a beautiful wall of tags where visitors were invited to write how they felt in response to the exhibition.

In particular, what really caught my interest was the way that science, which people have so much faith in as the true confirmer of facts, was used to prove that what people dismiss as unnatural and unscientific is actually a scientifically demonstrable part of nature. As anthropologists, we all know about the politics of knowledge production, and how dominant narratives reflect hegemonic understandings. I like to think of anthropology as a ‘potentially revolutionary praxis, because it forces us to question our theoretical presuppositions about the world, produce knowledge that is new, was confined to the margins, or was silenced.’ (Alpa Shah 2017) I have become frustrated countless times in the process of trying to explain this to my STEM friends. I felt enlightened by the way the exhibition had harnessed the respect that science receives as ‘the ultimate legitimate authority’ to expand people’s thinking.

The combination of art, science, and nature made complex academic ideas so digestible, concise, and clear while maintaining their richness and not being overly reductive. Throughout my anthropology degree, I have encountered so many fascinating ideas that I wish were more present in mainstream discourse. As I painstakingly make my way through pages and pages of dense critical theory about gender and sexuality for my course on gender and kinship, I often fear that these ideas, which are so important and so potentially world-altering, only ever circulate in academic circles. I often find myself wishing that anthropological theorists wrote more like David Graeber; unpretentious, understandable, and accessible.

I love the work of theorists like Judith Butler and Gayle Rubin, and don’t want to understate or undermine the immense value of their writing for the anthropology of kinship, sex, and gender. But spending my summer watching a range of audiences from queer university students well-versed in countering conventions, to more conservative older visitors, all engaging with queer theory in diverse and open-minded ways, gave me a renewed sense of hope about the power that anthropology contains to challenge the preconceived assumptions that people carry with them in their perception of the world. The average non-anthropology-student is most likely not going to read an extensive, complex analytical deconstruction of heteropatriarchal societal structures, but they can most definitely engage with these ideas if they are made comprehensible and approachable.

I wanted to include a special mention of a contributor to the exhibition: Drag performer and anthropologist, Cheddar Gorgeous (aka Dr Michael Atkins), who focuses on disrupting gender conventions, contemporary urban gay spaces, and using graphic novellas as a form of ethnographic storytelling – Their work has been inspiring to me by demonstrating how an anthropologist can ensure their counter-conventional work isn’t limited to the academic sphere.

During that summer, I lost count of the amount of times I heard people say ‘I’ve never thought of it like that before.’ By definition, any ideas which challenge dominant understandings are going to be initially limited in their reach, and their merit derives from not being mainstream; but gatekeeping anthropological knowledge with complicated jargon doesn’t do anyone any favours. It has become clear to me that embracing interdisciplinary methods of presenting the knowledge that anthropology produces is an effective way to expand the reach of our discipline’s vital insights.

References:

Ethnography? Participant observation, a potentially revolutionary praxis – Alpa Shah (2017)

Piers Morgan rages over Kew Gardens ‘Queer Nature’ Event – Pink News (2023)

https://www.thepinknews.com/2023/09/07/kew-gardens-queer-nature-piers-morgan/