Whose peace, whose history? Reflections from two museum visits in Seoul: the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum and the War Memorial of Korea

By Elise Lee

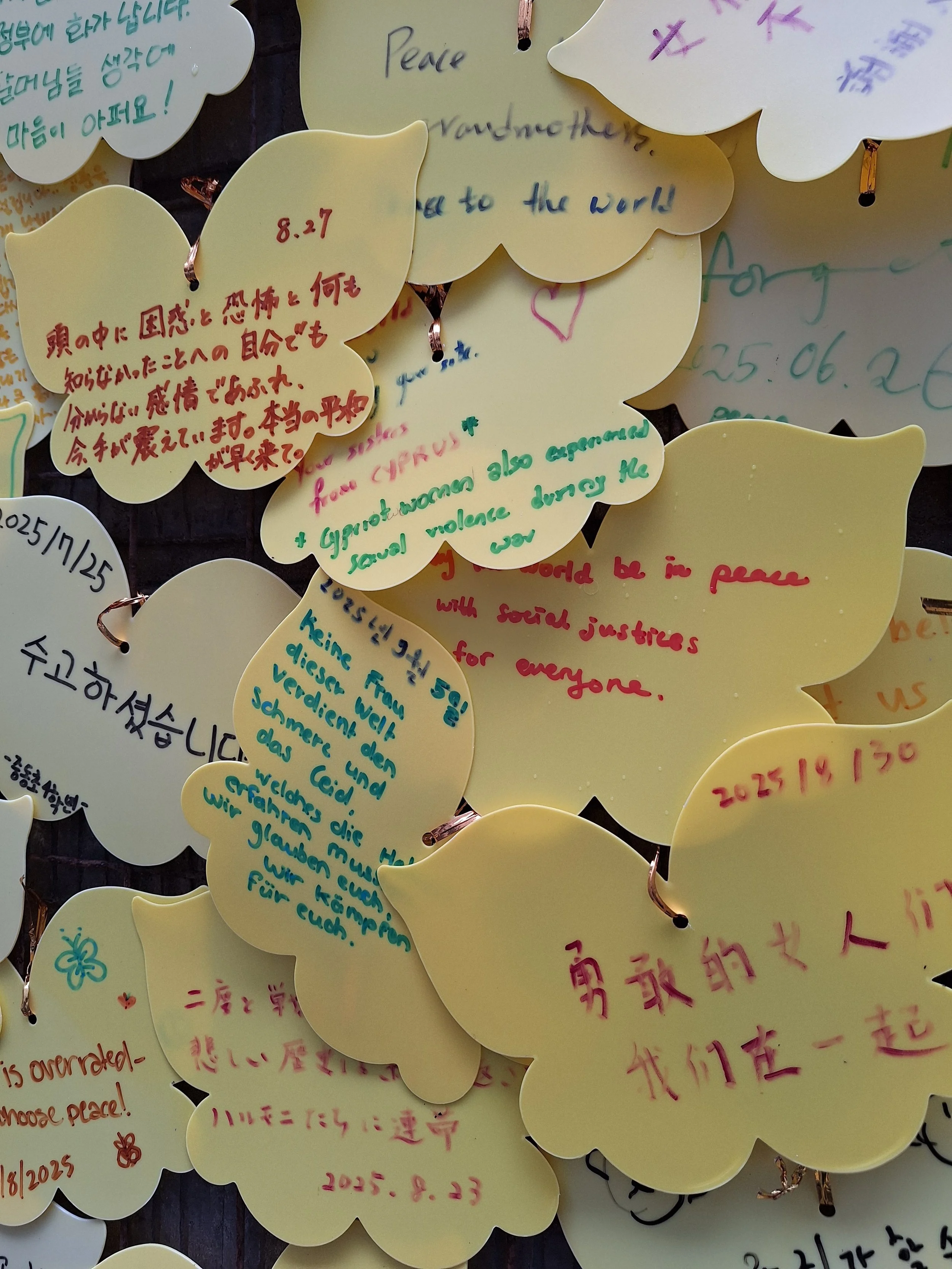

While travelling in Seoul on a rainy day, I walked uphill toward the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum. The street was quiet, unlike the crowded, spectacular tourist routes I had followed over the past few days. Following the paintings on the sides of the street, I arrived at a grey brick facade, covered with yellow butterfly notes bearing visitors’ messages of solidarity. Not monumental but intimate, the three-storey house unfolds a painful and long-silenced history of sexual slavery.

The visit raised questions which resurfaced a week later, when I visited another museum, the War Memorial of Korea. Whose history is being told here, and toward what vision of peace? How can hope, resilience and solidarity be cultivated while carrying historical trauma? Two museums, two memories. Both speak of war, violence and “peace”. Yet they imagine different moral worlds: one intimate, feminist, unsettling but reassuring; the other monumental, military, nationalist and masculine.

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum

As I opened the door, the small reception area was dark and quiet. A middle-aged woman behind the reception desk greeted me in Korean. Noticing my hesitation, she slowed her speech, shifting gently between Korean and English. When I told her I spoke “only a little Korean” as a foreigner, she smiled and replied gwaenchanh-ayo (it’s okay), patiently explaining the ticket price, audio guide and exhibition route. Then, she introduced the face printed on the ticket–the late Kim Bok-dong, one of the most prominent survivor-activists of Japanese military sexual slavery in WWII. She was referred to, alongside other victims, as halmoni (grandmother), a Korean kinship term with dignity and agency, instead of “comfort women”, a Japanese bureaucratic colonial category that reduced them to instruments of sexual exploitation in WWII.

The exhibition begins with a narrow gravel walkway that leads downwards. The crunch of stones underfoot, accompanied by the sound of gunfire, and the closeness of the walls create a bodily sense of confinement, ushering visitors into the halmonis’ suffering. Drawings made by survivors hang along the walls, guiding me deeper into the dimly lit basement where videos of the halmonis’ testimonies are played. In this dark, cramped space, I encountered the halmonis’ voices, their isolation and endurance and the heavy weight of history.

The next section opens into a brighter room displaying historical documents that reveal the scale and systematic organisation of Japanese military sexual slavery. It also traces the halmonis’ decades of activism: their struggle to break the silence, to demand accountability from the Japanese state, and to build solidarity in transnational movements against military sexual violence with those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Congo and elsewhere.

The Memorial Hall is the most saddening display. Names and dates of death on the bricks commemorate known victims. Victims whose names are unknown are also remembered, represented by black bricks. Hallam and Hockey (2001) argue that people manage relationships with the dead through materiality; memorials “deploy words in the service of a particular conception of memory and its relation to materiality” (171). Visitors do not encounter an abstract category of “comfort women”, but a tangible wall with names engraved that must be faced and walked along. Even for bricks without names, they give physical weight to the invisible deceased, bringing the “absent” present. According to the audio guide, despite its grief, the Memorial Hall is deliberately located at the brightest part of the museum, exposed to sunlight as a symbol of hope. As a site of ongoing relation, the hall makes the deceased halmonis visible and spatially orients the dead toward the living.

Hope also emerges from two special exhibitions, from the legacies of Kim Bok-Dong and the surprising solidarity between Korean halmonis and Vietnamese survivors of sexual violence committed by Korean soldiers during the Vietnam War. In the outdoor area below, the museum confronted a history rarely centred in South Korean public memory, featuring the testimonies of Vietnamese victims. Here, the familiar national narrative of Korea solely as a victim of colonial violence is unsettled. Koreans appear not only as those who were “wronged”, but also as those who “wronged” others.

The survivor-activist Kim Bok-dong said to Vietnamese survivors: “We are the same victims of Asian wars. The only difference is that they were harmed by the Korean military.” And another quote: “I am sorry, as a Korean citizen, that the Vietnamese suffered like us (halmonis) because of the Korean military. I will continue to support survivors of sexual violence around the world so that they may be consoled, even a little.”

The late Kim Bok-Dong’s lifetime dedication to peace, activism and women’s rights is inspiring, showing “victims” are not passive but resilient. For her, peace means a world where people “live comfortably without war”. She also extended her activism beyond South Korea’s national borders by establishing scholarships for ethnic Koreans in Japan, supporting Vietnamese survivors, and creating the Butterfly Fund to redirect Japanese government reparations to other survivors of wartime sexual violence worldwide.

The weekly Wednesday Demonstration in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul continues till today, demanding recognition and accountability. Activism seems like a long road; it is work, but it also works.

Before I left, I handed back the audio guide. The same reception woman asked gently, “Did you see everything well? Did you also visit the Vietnam section outside?” The exhibition’s heaviness lingered, but so did the warmth of the receptionist’s voice, Kim Bok-dong’s legacy and the hope cultivated by this space of memory and resilience.

As I left, I also left a butterfly note. These notes are a form of “memory writing”, a “hybrid” entanglement of “material objects” and “embodied practices” (Hallam & Jockey 2001: 177). The butterflies form a growing network of solidarity between halmonis, activists, other supporters, and those suffering abuses across the world. As each visitor leaves their note, they enter into a dialogical space that extends beyond the current time-space. The butterflies address both the living and the dead, and connect the past and future visitors.

A week later: the War Memorial of Korea

Again in the rain, I visited the War Memorial of Korea. I immediately felt the contrast between it and the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum. Where the feminist museum is only as big as a large house, this War Memorial has multiple indoor main halls and a large outdoor space with statues and flags. Its architecture is angular and grand.

Built to commemorate the Korean War and also in the hope of “peace”—but as in the “peaceful reunification of North and South Korea”—the War Memorial also serves as a pedagogical site for national military history. When I entered the museum, I encountered a group of young men in military uniform, who I believe were conscripts on a visit to learn about the military history and the Republic of Korea armed forces they were part of.

There is also a Memorial Hall. It honours soldiers and policemen killed in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Like the Memorial Hall in the War and Women’s Human Rights, it was quiet. The installations and sculptures titled “the Spirit of the Nation”, “Traces of Patriotism”, and the “Creation” represent the Republic of Korea, the desire for one non-separated nation, and hope despite past destructions. The deaths are sacrifices made for national unity.

The exhibitions display weaponry and war histories from the Three States era (from the 1st century BCE) to the present. The Korean War is framed through international alliance and sacrifice, emphasised as the United Nations’ first large-scale peacekeeping coalition, supported by 63 countries. Here, “peace” is defined through national security and collective military effort.

I specifically remember a gallery titled “From a Recipient Country to a Donor Nation.” It presents South Korean history as linear progress: from need to self-sufficiency, from being “helped” to becoming a “helper”. In its narration, with support from 63 countries, the Republic of Korea has risen from a war-torn aid recipient to a G20 economy and contributor to UN peacekeeping missions in places like South Sudan and Lebanon. I thought: isn’t this the teleology of modernity that anthropology so often critiques?

South Korea casts its past as “less developed,” only to reposition itself as a “modern” nation now able to assist the “Third World.” As anthropologists such as Wolf (1982) and Escobar (1995) critiqued, Eurocentric developmental narratives reproduce a single historical trajectory of progress that naturalises global hierarchies. Reinscribing this logic, South Korea adopts the very framework that once positioned it as lacking to advance itself geopolitically. As Cho Han (2000:59) notes, in South Korea, “after the 1970s, the discourse of nationalism was directly connected with economy-first policies that sought the development of a powerful nation.” Within this discourse, becoming a “donor” signals entry into modernity and geopolitical power. “Help” appears neutral and benevolent, while obscuring unequal power relations; “peace” emerges as the outcome of linear progress and geopolitical stability.

The Vietnam War is featured in the exhibition “Expeditionary Forces Room”, but only as a chapter highlighting the Republic of Korea's contributions to medical care and reconstruction. As expected, the dark history of sexual violence committed by Korean soldiers against the Vietnamese is absent. This museum, after all, is a patriotic space dedicated to honouring those who devoted their lives to the nation in wars from the past to the present, not a place for self-criticism. National guilt is not contained, tolerated or relieved by the space, but simply an elephant in the room, or perhaps the elephant is not even here.

Two narrations, different “sacrifices”

National museums reflect a form of politics that might be called sacrificial nationalism. The nation is imagined as something that must be sustained through the offering of lives. At the War Memorial of Korea, soldiers’ deaths are framed as meaningful sacrifices made for national survival, unity, and progress. Loss is not presented as tragic alone, but as necessary and honourable. Peace, here, is not the absence of violence but is achieved through disciplined bodies, military alliances, and a heroic willingness to die for the nation. The state presents military interventions, UN peacekeeping missions, and development aid as national generosity while obscuring whose labour, lives, and sufferings make these “sacrifices” and national glory possible.

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum exposes the exclusions built into this sacrificial nationalism. The halmonis’ suffering does not fit the heroic narrative of chosen sacrifice. Their bodies were not offered to protect the nation, but taken through imperial and militarised violence that rendered women’s lives expendable. This suffering is difficult to assimilate into nationalist memory because it disrupts the image of sacrifice as noble. By centring halmonis’ testimonies, sufferings and activism rather than heroic death, the museum does not convert gendered violence into a redemptive national story. Instead, it speaks of halmonis’ “sacrifices”—including victims who “sacrifice” their lives traumatically and survivors who “sacrifice” their time and effort in activism—as a political call to confront ongoing abuses of women’s human rights worldwide.

Offering a feminist critique, Cho Han (2000:57) argues that South Korea’s “compressed” economic growth produced “grand statepower and patriarchal families, but no citizens or autonomous individuals,” even as such “national persons” enabled the rapid growth. The halmonis sit uneasily within the nationalist discourse. Their activism can be absorbed into nationalism when it aligns with the discourse of anti-Japanese imperialism and helps cast South Korea, with its Butterfly Fund, as a global “helper” of other “Third World” women in need of “saving”. Yet, halmonis did more, especially with the inclusion of Vietnamese victims of Korean soldiers’ sexual violence, shattering the patriarchal nationalist discourse.

Two narrations, but both speak of “peace”

Both museums narrate the past of wars and imagine a future of peace. One centres on bodily abuses, trauma and sexual violence. The multisensory curation helps museum visitors step into the halmonis’ shoes (which is not to say the halmonis’ experience is translatable or anyone can simply “understand” or “feel” the same merely via an exhibition). Peace and hope emerge from feminist resistance and activism. The other centres on the nation, weaponry and military alliances, embedding peace within militarised security, state sovereignty and geopolitics.

Both speak of transnational solidarity; one through shared struggles against sexual violence, the other through multinational military cooperation. Both claim hope. Both speak the language of “peace”. Yet whose peace, and at what cost?

Can history be told without fixing permanent categories of victims and perpetrators? Solidarity is a step towards “peace”, but to avoid new exclusions, we have to be aware of who we are building solidarity with and not with. Perhaps peace is not a singular horizon but a contested moral project, shaping whose suffering counts and whose is rendered invisible.

It’s a long road to freedom and peace. And I have no answers. But I think to speak of peace, we must first ask: peace for whom, and narrated by whom? In museums and other educational spaces, this begins with listening differently, critically and attentively to silenced voices.

It’s raining, and it’ll rain again, but there is sunshine. The question is whether we can learn to see it through the shadows of rainclouds.

Bibliography

Cho Han, H.-J. 2000. ‘You are entrapped in an imaginary well’: the formation of subjectivity within compressed development - a feminist critique of modernity and Korean culture. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 1, 49–69.

Escobar, A. 1995. Encountering development: the making and unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Hallam, E. & J. Hockey 2001. Death, memory and material culture. Oxford: Berg.

Korea War-memorial Organization 2023. The War Memorial of Korea (available on-line: https://www.warmemo.or.kr:8443/Eng/index, accessed 8 February 2026).

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum 2024. The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum (available on-line: https://womenandwarmuseum.net/233, accessed 8 February 2026).

Wolf, E. 1982. Europe and the people without history. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.