Constructing Power: The Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in the UAE

Constructing Power: The Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in the UAE

by Daniel Guthrie

McQue, K. (2020) Social distancing is impossible in the cramped living quarters of Dubai’s labour camps, The Guardian. Dubai: The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/sep/03/i-am-starving-the-migrant-workers-abandoned-by-dubai-employers

The Qatar World Cup made the treatment of migrant labourers in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) a topic of global discussion. From the widely circulated Guardian article claiming 6,500 migrant workers had died since Qatar had been deemed hosts in 2010 (Pattison, 2021), to FIFA president Gianni Infantino’s baffling assertion on the eve of the tournament that he feels ‘like a migrant worker’ (Page, 2022), the plight of the migrant labourer outside the West has perhaps never had this much attention. Whilst it is Qatar that has received the most recent coverage, it is the UAE which has the largest catalogue of discourse on the issue, over the longest span of time. The issue is especially pressing given the number of migrant workers within the UAE – estimates consistently put migrant labourers as around 90% of the UAE workforce, with some 500,000 of those being construction workers (Sönmez et al., 2013). To grasp why this exploitation is so prevalent, there needs to be an understanding of both the unique systems of labour management and worker treatment that operate within the UAE, and an understanding of theories relating the power over death. Elements of Foucault’s concept of biopower (especially regarding anatomo-politics) and Berlant’s concept of slow death will be utilised to locate power in the government-employer-migrant construction worker relation, ascertaining what has led to the current situation of exploitation that is now under the global spotlight.

The positionality of the migrant construction labourer

Firstly, the position of migrant labourers must be understood. Migrants enter the GCC’s labour market through the kafala system. Within this structure, migrants must be sponsored by a specific employer to gain a work contract, enter the state, and obtain a residence. To afford transit, funds are borrowed or generated by the sale of homes or livestock (Sönmez et al., 2013). In most of the cases this obviously creates an enormous financial pressure on the labourer since they often find themselves with huge debts and with a family reliant on their work at home. Debts can be as high as US$4000; an unsettling figure when construction workers receive, on average, the equivalent of US$175 a month (Ghaemi, 2006: 7). Most significantly for the discussion of power, the kafeel (sponsor) is essentially wholly responsible for the worker. They dictate their employment and residency, have the responsibility to inform authorities of changes to the contract, and can even restrict workers mobility or changes to employment (Ngeh & Pelican, 2018: 172). The government of the UAE has made a large part of the governing of migrant workers the responsibility of employers.

The Kafala system is widely regarded as corrupt, so much so that Bahrain, another country in the GCC, prohibited it in 2009 – the minister of labour referring to it as “not differ[ing] much from the system of slavery” (Mahdi, 2009). Postcolonial philosopher Achille Mbembe defined the state of the slave as “a triple loss: loss of a “home,” loss of rights over his or her body, and loss of political status” (Mbembe, 2003: 21). Migrants under the kafala system leave their home and move into their employer’s labour camp. Their employer has near-total power over the movements and existence of their employees. They will often find their passports confiscated, under the guise of this being customary within the kafala system (Sönmez et al., 2013); in reality, it is to control their movements and ensure they do not attempt to return home.

Further control is exerted in several ways. A significant method is the retaining of workers’ pay, an issue that has led to numerous strikes, some involving hundreds of workers over six months unpaid wages (Dajani, 2021). Given the immense financial pressure on migrant labourers, this can be destructive to their lives at home, and this immense power can be exercised on the employer’s whim. Migrants have no voting rights in the UAE, as the government selects which citizens can vote in each election, and citizenship is exclusively reserved for nationals, or specific expats. Additionally, employers purposefully aim to hire labourers who cannot speak Arabic, so they cannot read the contracts they sign, or even converse with non-migrants (ICFUAE, 2019: 9); some go further, and hire from a wide range of countries and locations so that their workers cannot communicate (ICFUAE, 2019: 9). The labour camps set up to house migrants are located on the peripheries, so that they are geographically segregated from the privileged classes of the UAE (Hamza, 2015: 90). They report feeling socially excluded from entering parks and shopping centres, saying they are “not people of the city, we live in a labor camp” (Hamza, 2015: 101). Migrant workers experience a holistic loss of bodily autonomy and personhood as they are created as a disposable population. Their conditions are more akin to slavery than free employment.

Where the government does play a role in the wellbeing of construction labourers, it is often insufficient. The law governing workplaces is the UAE Federal Law No. 8 of 1980 (colloquially referred to as the ‘Labour law’), and it is enforced by the Ministry of Labour. The Labour Law explicitly prohibits unionising and striking (Federal Supreme Council, 1980), criminalising any preventative measures by workers to effectively ensure the enforcement of their legal rights. The Ministry of Labour is responsible for ensuring regulations are followed by both employers and employees; however, in 2006 it was reported that “140 government inspectors were responsible for overseeing the labor practices of more than 240,000 businesses employing migrant workers” (Ghaemi, 2006; pg. 6). Construction businesses number around 6,000 (Seghedoni, 2017), meaning that, proportionally, there are less than 4 inspectors for the inspection of every aspect of a construction industry which employs more than 500,000 workers. Furthermore, these inspectors are mainly concerned with the residential situation of the workers, and workplace concerns and hazards are not prioritised (ILO, 2010). There are no standardised labour inspection procedures (ILO, 2010).

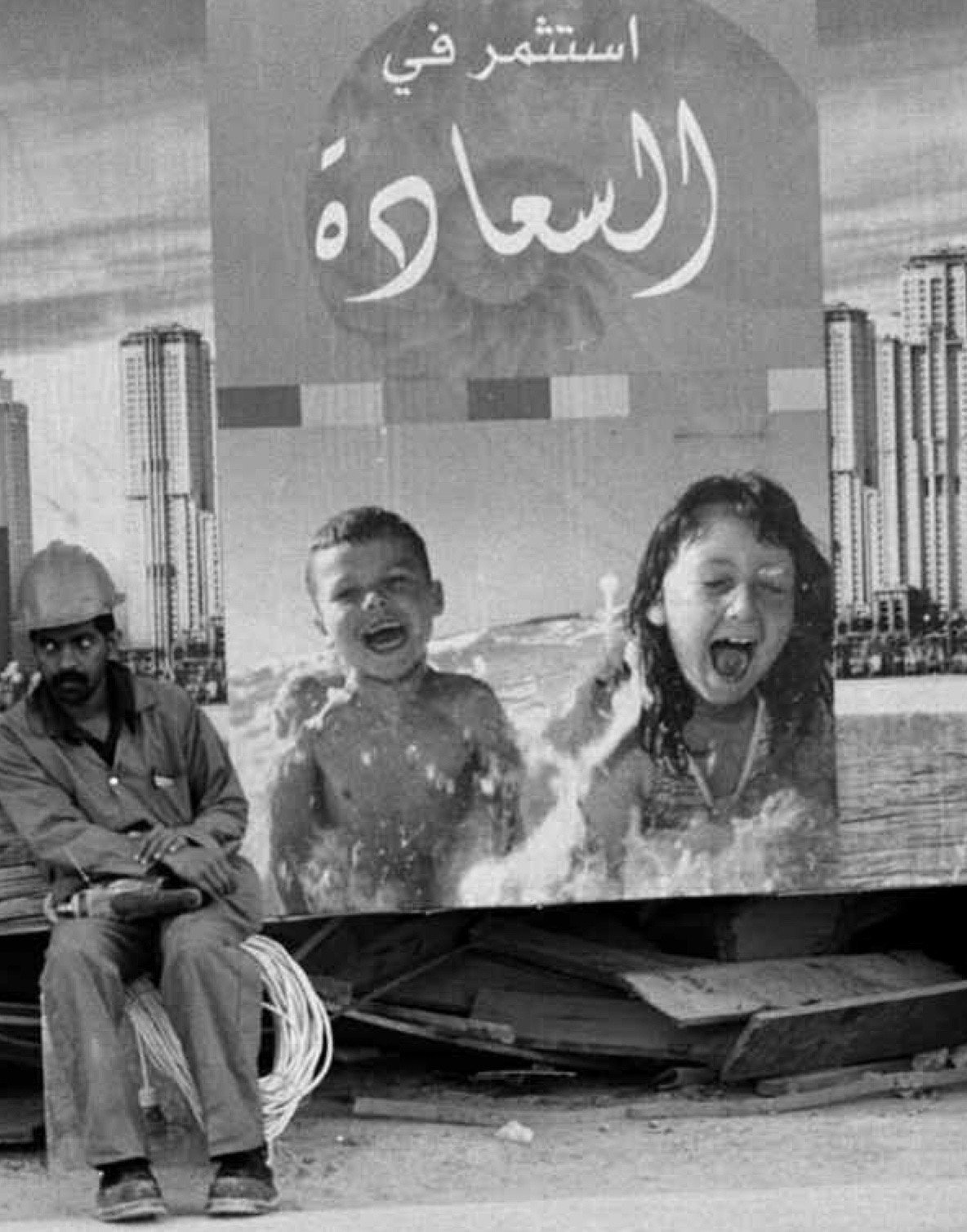

Picture 1: A foreign worker waits for the company's bus service to take him home after a day at work (2006) Building Towers, Cheating Workers. London, London: HRW

Picture 2: Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, December 8). Burj Khalifa. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Burj-Khalifa

Working conditions in the UAE are dire. During the construction of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, the average worker worked 12 hours a day, 6 days a week (ICFUAE, 2019: 11). Death of migrant workers is a common occurrence. The story of Julhas Uddin, a migrant labourer who died when he was instructed to enter a sewage line without an oxygen cylinder (McQue, 2022), is no outlier. One report found that between 2010 and 2019, an average of 5866 non-nationals from south and southeast Asia have been dying every year in the UAE (Vital Signs, 2022: 25). Whilst not all of these would’ve been construction labourers, and not all of these may have been in the workplace, several factors must be considered: construction is the most dangerous position they will be employed for; migrant workers are often younger than 40, so the chances of them dying of ‘old age’ are small; and just because a worker didn’t die on site, it does not mean that unsafe working conditions, e.g. working with dangerous chemicals or no filter masks, did not cause or lead to their death. This report also doesn’t account for migrant labourers from Africa, a growing demographic. Perhaps more shockingly, “1 out of every 2 deaths is effectively unexplained… instead using terms such as “natural causes” or “cardiac arrest”” (Vital Signs, 2022: 26). In addition to this, there are many unrecorded deaths, meaning the actual figures are likely higher than the documented 5866 a year. It is apparent that the bureaucratic structure has such disregard for the lives of migrant labourers that even their deaths are regarded as of little importance. Furthermore, there are no official figures on workplace injuries; however, it is certain that they are even more commonplace.

Thus, the positionality of the migrant construction worker is one of near-constant peril. Under immense financial pressure, they are stripped of their identifying documents, and placed in high-risk, low-wage work, where their rights border on non-existent, and they are legally prohibited from mobilising. There is no free market in the UAE – due to the kafala system, they cannot leave their employer to join a competitor, meaning the employer can treat them however they please. The government has apathy for their wellbeing, from washing its hands of many bureaucratic duties, to a woefully inefficient inspection structure. Prohibitions on mobilising, and ineffective and poorly organised modes of inspection, lead to situations where employers have almost total discretion as to the treatment of their employees, and employees are powerless to resist. They cannot even be trusted to give an accurate account of death, a consequence of workplace abuse which looms over the construction workers, higher even than the glittering cityscape they are building.

The death of the migrant construction labourer

For a complete analysis of the power that employers exert over their employees, the most insightful analytic will be a synthesis of two theories relating to power and death. The first will be aspects of Foucault’s theory of biopolitics - power as being a ‘right of seizure’, the justification of death as “on behalf of the existence of everyone” (Foucault, 1978: 137) and “the anatomo-politics of the human body” (Foucault, 1978: 139). The second will be Berlant’s theory of ‘slow death’- “the physical wearing out of a population and the deterioration of people in that population that is very nearly a defining condition of their experience” (Berlant, 2007: 754). Berlant’s framework essentially fills in the gaps of Foucault when dealing with oppressive systems that have become the norm for certain populations.

Reading Foucault in accordance with the exploitation of migrant labourers provides a useful understanding of the development of gaining power. The right of seizure is the right to seize “things, time, bodies, and ultimately life itself” (Foucault, 1978: 136). As demonstrated above, employers in the UAE both actively (through the kafala system, the retaining of passports and the inhumane workload) and passively (through spatial containment and social isolation) seize control over the personhood of the migrant construction worker. Their deaths are deemed to be a non-event – ‘natural causes’ is scrawled as the reason for death, and there is always another worker to take their place. This right of seizure is demonstrated by employers and condoned by the government.

Foucault’s theory that death is justified as ‘on the behalf of everyone’ must be skewed slightly for this subject. His example rests on the premise of war, detailing how slaughter is justified “in the name of necessity” (Foucault, 1978: 137). The UAE is not engaged in any war in this sense – however, the deaths of these construction workers is on the behalf of those already residing in or attracted to the UAE by low tax rates and the futuristic appeal of skylines such as Dubai’s. Here, the government has created an image which employers realize – that of the UAE as a financial hub of the future, complete with soaring glass towers and labyrinthine shopping centres, a monument to consumption and consumerism. Death no longer must be justified in the name of necessity; it can now be justified in the name of opulence.

Anatomo-politics makes up the individual half of the theory of biopolitics. It focuses on the reconstitution of man as “a machine: its disciplining, the optimization of its capabilities, the extortion of its forces” (Foucault, 1978: 139). Its direct relation to power is in the extent to which the powerful body can perform this reconstitution. In making man a machine, it necessitates dehumanisation, as the valuation of the individual becomes what they can do, and how effectively they can do it. Migrant workers are dehumanised and broken down to such an extent that they do not feel part of the population – the government does not concern itself with their wellbeing, and they are herded to labour camps on the edges of cities. Their life becomes work – they do not have time for anything else, they cannot access any space that isn’t the camp or the construction site. The individual is not only deemed a machine but comes to think of themself as a machine. A machine cannot die – it can only break, and with so many other tools at the employer’s disposal, the broken machine is discarded.

Foucault notes that power’s highest function may have shifted; it is “no longer to kill, but to invest life through and through” (Foucault, 1978: 139). The employers of the UAE can push life to its limits, to the point of death in many cases. They need not exercise the threat of death as a punishment, as their workforce has already been manipulated and reconstituted to have no other alternative – obey to live has replaced obey or die.

Despite its usefulness, Foucault’s theory does have its limits. Crucially, it focuses on points of crisis, such as war or genocide, as being the situations when the ultimate expression of these forms of power come into being. Berlant offers a more nuanced perspective, stating that slow death is “a defining fact of life for a given population that lives it as a fact in ordinary time” (Berlant, 2007: 760). Construction workers in the UAE are not only physically worn down, but consciously deprived of basic liberties; so much so, that they internalise the fact that they are not part of the public, but are instead simply their job title. Despite protests, and reform in other GCC states, there is no indication the government will do anything to help them. The Ministry of Labour fails the migrant worker at every conceivable turn, so much so that its presence becomes phantasmic; the reality for the migrant worker is dominated slow death, the deterioration normalised to justify the push towards the future.

Another way in which Berlant phrases slow death is “structurally motivated attrition” (Berlant, 2007: 761). This definition again builds on Foucault, as it recognises that the distribution of power may not exclusively be top-down – it can be an intersectional attempt to degenerate certain persons. Both the government and employers disregard the humanity of the migrant construction worker; agents at multiple sites are complicit. Additionally, the structural motivation behind this treatment helps to normalise it, especially when this vast group of the population is voiceless by design.

Conclusion

To conclude, the migrant construction labourer is dead by design. They have been stripped of their identity, stripped of their humanity, and mechanised; and this process has been met with mostly indifference. The government of the UAE has absconded all responsibility for their livelihood, and left them in the care of employers who engage in a system comparable to slavery to obtain their workforce, and segregate them from the rest of humanity, and human contact, to further reduce their personhood. When one dies, if the death is even recorded, it does little to change practices; construction activity in the UAE is on an upwards trajectory (Illankoon, 2022), and this is only likely to continue. The normalisation of their subjugation has led to their lives being disposable, and those with the power to change the system either are disinterested in changing it, or actively participating in maintaining it.

Further work can be done – issues of racism are also reported to be prevalent, as are cases of gendered discrimination, leading in some cases to forced prostitution (Sönmez et al., 2013). Additionally, this work focuses exclusively on the construction sector – a comparative with the treatment of domestic or hospitality workers could illuminate other manners in which the power to subjugate and oppress is used. It is likely that the GCC will only become a more and more crucial area to understand as time goes by – they, by no account, are planning on slipping into obscurity, continually developing their hospitality sectors and tourist draws, the World Cup being the most major recent example of that. The forms of power that operate within the UAE – the mechanisms by which they came to be and the methods which reproduce them – must be understood if any effective action is going to be taken against them.

Globally, the erosion of personhood and domination over the humanity of an exploited workforce must be studied. These practices are not unique to the UAE and exist far outside the sphere of construction. Utilising the framework presented here - the production of the worker, and what impact this has on their perceived humanness, read alongside theories of power production – could provide for a more developed understanding of the human cost of progress.

Bibliography

The abuse and exploitation of migrant workers in the UAE (2019) ICFUAE. ICFUAE. Available at: https://www.icfuae.org.uk/research-and-publications-briefings/abuse-and-exploitation-migrant-workers-uae%C2%A0 (Accessed: December 22, 2022).

Berlant, L. (2007) “Slow death (sovereignty, obesity, lateral agency),” Critical Inquiry, 33(4), pp. 754–780. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/521568.

Dajani, H. (2021) Construction workers strike on Abu Dhabi's Reem Island, The National. The National. Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/construction-workers-strike-on-abu-dhabi-s-reem-island-1.948820 (Accessed: December 20, 2022).

Federal Supreme Council and Federal Supreme Council (1980) UAE Federal Law No. 8 of 1980. Abu Dhabi: UAE Official Gazette.

Foucault, M. (1978) The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. 1st edn. New York, New York: Pantheon.

Ghaemi, H. (2006) Building Towers, cheating workers, Human Rights Watch. HRW. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2006/11/11/building-towers-cheating-workers/exploitation-migrant-construction-workers-united (Accessed: December 16, 2022).

Hamza, S. (2015) “Migrant Labour in the Arabian Gulf; A case study of Dubai,” Pursuit, 6(1), pp. 81–133.

Harmassi, M. (2009) Bahrain to end 'slavery' system, BBC News. BBC. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/8035972.stm (Accessed: December 20, 2022).

Illankoon, K. (2022) Middle East construction gains momentum despite supply chain disruption and rising construction costs, Construction Business News Middle East. Construction Business News Middle East. Available at: https://www.cbnme.com/analysis/middle-east-construction-gains-momentum-despite-supply-chain-disruption-and-rising-construction-costs/ (Accessed: December 18, 2022).

ILO (2010) United Arab Emirates, International Labour Organization. ILO. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/country-profiles/arab-states/emirates/WCMS_150919/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed: December 21, 2022).

Mahdi, M. (2009) Bahrain: Decree 79 aims at ending sponsor system, International Labour Organization. ILO. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/news/WCMS_143009/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed: December 21, 2022).

Mbembe, A. (2003) “Necropolitics,” Public Culture, 15(1), pp. 11–40. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11.

McQue, K. (2022) Up to 10,000 Asian migrant workers die in the Gulf every year, claims report, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/mar/11/up-to-10000-asian-migrant-workers-die-in-the-gulf-every-year-claims-report (Accessed: December 21, 2022).

Ngeh , J. and Pelican, M. (2018) “Intersectionality and the Labour Market in the United Arab Emirates: The Experiences of African Migrants.,” Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 143(2), pp. 171–194. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26899770 (Accessed: 2022).

Page, M. (2022) FIFA president's 'I feel like a migrant worker' speech misleading, Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/11/21/fifa-presidents-i-feel-migrant-worker-speech-misleading (Accessed: December 20, 2022).

Pattison, P. (2021) Revealed: 6,500 migrant workers have died in Qatar since World Cup awarded, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/feb/23/revealed-migrant-worker-deaths-qatar-fifa-world-cup-2022 (Accessed: December 20, 2022).

Seghedoni, S. (2017) United Arab Emirates: Where construction never sleeps, ceramica.info. Tile. Available at: https://www.ceramica.info/en/articoli/united-arab-emirates-where-construction-never-sleeps/ (Accessed: December 21, 2022).

Slater, J. and Colville , E. (2014) Collective Bargaining Rights of employees in the UAE, Global Workplace Insider. Available at: https://www.globalworkplaceinsider.com/2014/04/collective-bargaining-rights-of-employees-in-the-uae/ (Accessed: December 16, 2022).

Sönmez, S. et al. (2013) Human rights and health disparities for migrant workers in the UAE, Health and Human Rights Journal. HHR. Available at: https://www.hhrjournal.org/2013/08/human-rights-and-health-disparities-for-migrant-workers-in-the-uae/ (Accessed: December 18, 2022).

Vital Signs (2022) THE DEATHS OF MIGRANTS IN THE GULF. rep. Vital Signs. Available at: https://fairsq.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Vital_signs-report-1.pdf.