Intimacy Economies and Reality Dating TV Shows

Reality Dating TV shows have captured the attention of the general public and academia alike. Infused with entertaining conversations, beautiful bodies and details into personal life, there is something in these shows for everyone. Many dating reality TV shows have received the same critiques that other reality TV has, described as vapid, silly, and superficial. But academia has shown that shows like this filled with false realities have small nuggets of ‘truth’, not just in their content but in their continued existence. Although seemingly distanced from reality, they reflect societal attitudes to romantic relationships and more.

The hyper-surveillance in many of these shows makes the audience into something akin to an anthropologist observing the field site and the behaviour of participants. ‘Love Island’ itself perfected this formula, placing a group of strangers into one villa with nothing to do but get to know other participants, whilst their interactions are streamed on TV. A ‘Love Island’ hierarchy is created in these mini societies, at the top of which there are the ‘strongest couples’ and the most liked contestants within the villa. The beauty standards and behaviours that dictate this hierarchy replicate those which we see in the real world, as Eurocentric and heteronormative beauty standards shape contestants' dating habits and performances. What is also intriguing about these shows is their embeddedness in the wider capitalist context. The contradiction of being part of a profit-making industry yet simultaneously trying to portray love as removed from this is reflected in the participants’ attempts to disguise their motivations for participating in the shows. With prize money awarded to the favourite couples, contestants who show monetized motivations for wanting to win come across to audiences and fellow contestants as distasteful. Perhaps this highlights our inability to realize that money does often dictate our pursuits of love. ‘Love Island’ as a dating show started with the intention of making money, and the participants behaviours can’t be understood outside of this framework.

Love does not exist detached from a capitalist society, as it is embedded within it and shaped by it. The commodification of love propels consumerism and props up the entertainment and media industry. In terms of consumerism, jewellery brands often utilise public conceptions of romance to sell products. Major holidays like Christmas and Valentine’s Day propel the idea that love can be bought through gifting commodified products. Moreover, the romance film and tv industry has utilised romantic themes to keep audiences’ attention. Netflix shows like ‘Bridgerton’ combine the popularity of romance in fiction and the periodical film genre to capture our attention and keep us consuming. The ‘golden age of rom-coms’ from the 90s to the early 2000s brought in massive amounts of profits for mid-budget feature films. Notions of romance leak into almost every film genre within the entertainment industry, from dystopian films to murder mysteries. Romance is likely to be integrated into these stories because of its ability to capture the audience's attention.

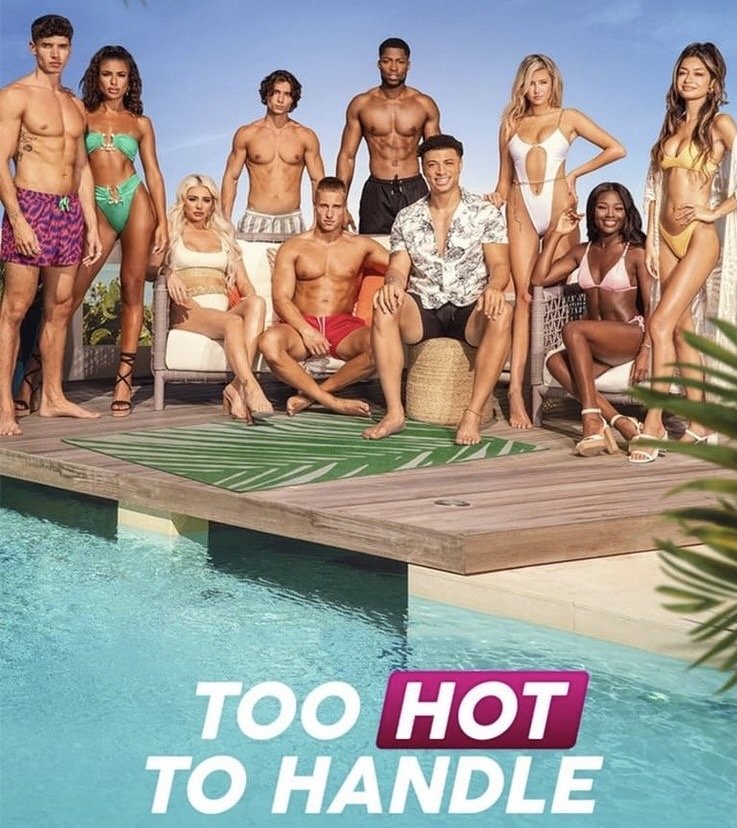

The show ‘Too Hot To Handle’, adds a fascinating spin to dating reality tv shows. The financial reward element is still strong, but punishment is also introduced. This punishment aspect is through the form of fines placed upon the contestants who act upon their sexual desires, so that sexual touching, kissing, sex, and self-gratification are banned. If they are caught on camera doing any of these things large amounts of money will be deducted from the prize fund. This aspect of the show can be both problematic and comical in that the contestants end up policing the sexual activities of one another. When individuals deviate from the rules, it's the responsibility of the group as a whole to discipline them for disobeying the rules of the retreat. If they don’t conform, they are kicked off the show. These rules about sexual behaviour in ‘Too Hot To Handle’ portray a popular theme, namely that withholding sexual intimacy is what creates meaningful connections. Within western societies, it is common to distinguish between sexual and meaningful relationships, stemming perhaps from a masculine idealisation of the need to discipline the body and natural urges to have a successful lifestyle. In such ideal lifestyle sexual temptations are erased or limited to a secluded sphere, while, often homosocial, relationships are valued as the essential ones. Take the idea of having sex on the first date - this is a debate that is constantly brought up when discussing dating habits. There is an assumption that having sex on the first date means that you cannot take the relationship seriously because it is purely sexual and not emotional. It reinforces the notion that ‘having sex too quickly’ weakens one's ability to create a long-lasting connection.

A picture of the cast of the second season of ‘Too Hot To Handle’

More than anything these shows reinforce pre-existing body and beauty standards rooted in heteronormative ideals. The men in the shows tend to have heavily muscular bodies, and gyms are installed within the villa to accommodate this. For women in this show, a slender body is essential, whilst emphasis on curves and hair colour is imperative. Hyperfocus on bodily details is another aspect of this, highlighted in the fact that when women enter the scenes, cameras zoom in on their bums and legs. When men enter, the focus is similarly on their stomachs and arms. Women and men are also separated, reinforcing heteronormativity. In the mornings men and women separate to debrief on the state of their relationships so far. Women get ready in dressing rooms whilst the men get ready in the bedrooms. Every arrangement is thus underlain by a strong distinction between men and women. When everyone gets ready for dates, the tradition stands that the girls descend the staircase whilst the guys stand and watch. The women are presented and displayed to the men, reinforcing the male gaze on feminine bodies and portraying men as objectifying agents.

As an avid watcher of these types of shows, I always find it interesting how societal issues manifest in these isolated villas that insist that they are detached from the outside world. It is clear however that these shows actually reproduce aspects of the intimacy economy at play in our wider society and operate as magnifying glasses into details of our Eurocentric, heteronormative and capitalist world.