DJINNS

The piece reflects on Morocco’s inherited relationship with the unseen, contrasting colonial rationalism with local cosmologies of fear, ritual, and coexistence. It’s written as a personal essay that moves between anthropology and lived experience—an attempt to explore what remains uncolonized in the Moroccan imagination.

by ADEMINU

I grew up terrified of the bathroom. Not because of the dark tiles or the smell of bleach, but because everybody whispered that the Jnoun lived there. Every flush was a negotiation with something unseen, every shadow in the corner a threat. You don’t sing or whistle in the bathroom, and you never stay too long with water running — everybody knows that. They told me the djinn like to sit near drains, they slip through faucets, they curl around wells, they hide in places we call home but never control. And yet the French textbooks in school never mentioned them. The textbooks told me about Voltaire and Rousseau, about humanist enlightenment, about the beauty of rational thought — meanwhile, at home, I knew the night itself was alive, I knew the world had a second skin that no philosophy could wash away.

The djinn are not metaphors. They are not fairy tales. They are the reason I never poured hot water without warning the air first. They are the reason I never picked up stones from the ground without whispering bismillah.

Always “bismillah,” always a soft murmur to announce yourself. It was etiquette, almost like knocking before entering someone else’s home. Because every corner of Morocco could belong to them. The field, the mountain, the seashore — none of it was empty. We were never alone.

Morocco’s coasts are crowded with tourists, sunburned bodies and umbrellas. But the sea at night belongs to someone else. Fishermen whispered that certain waves are not natural, that sometimes the water rises because something huge stirs beneath. There are stories of men pulled under by hands that were not human, of voices singing from the black horizon. You cannot convince a fisherman to whistle on the water — it is asking for disaster.

The mountains had their own guardians. Tales of caves where entire Jnoun tribes lived, tribes older than Morocco itself. Shepherds spoke of hearing drums echoing from inside cliffs, of goats vanishing without a sound. There were paths you did not take alone, no matter how bright the sun, because brightness does not matter to them. They live in daylight too.

There were rules about thresholds. Thresholds are not lines — they are lungs, breathing two airs at once and pulling you into the space between worlds. Never stand too long at the doorway, especially after sunset. Doors are weak places, open veins between here and elsewhere. My grandmother would hiss at me if I lingered with one foot inside and one foot outside: “Move, child, don’t let them notice you.” Even now, when I pause too long at a door, I can feel something watching. These rules are the first language of the world that cannot be seen.

Standing too long is not hesitation, it is conversation. The air shifts when you ignore it, like something unseen tilting its head toward you. Growing up in Morocco means learning to walk a tightrope between the worlds, learning that fear can guide, that respect can shield, that presence is not a choice but a way of breathing. Thresholds teach you this before language does — a quickening in the spine, a warning stitched into the air — the kind of lesson you understand with your body long before your mind catches up.

Shoes mattered too. You never left them upside down. An overturned shoe was a provocation — like baring your teeth at them and daring them to strike. I remember older relatives who would stop mid-conversation just to fix a sandal that had tipped the wrong way. You couldn’t ignore it. You couldn’t leave it. A careless shoe was a declaration of war to the Jnoun.

Iron was always sacred. They told us iron burns them, wounds them, keeps them away. My grandmother would slip a small nail into the baby’s pocket before sleep, as if the child’s body were a battlefield. Blacksmiths were whispered to have special protection — how else could they hammer metal all day and not go mad?

Salt too. Always salt. My aunt would scatter it at the threshold of a new house, saying it was to blind them, to keep them spinning in circles. Science said salt was for flavor. We knew better. Salt was for survival.

You think colonialism is the biggest scar, but no, the oldest wound is older than the French, older than the Arabs, older than the Romans — the oldest wound is the one that keeps us looking over our shoulders at night, the wound of sharing space with the invisible. And the irony is that the wound is both refuge and trauma. We inherit fear the way other families inherit land — passed down and lived in. It soothes us and scars us at the same time, because growing up with the djinn means growing up inside a world that holds you and haunts you in the same breath.

And that’s exactly why they slip past every empire that tried to tame us. The djinn do not care about borders, they do not care about passports, they move faster than the World Bank and the IMF, they slip into wells and houses and children’s dreams. They are the true empire here.

The French taught us Descartes, “I think therefore I am,” but my grandmother taught me “don’t stand at the threshold after sunset, or you’ll invite them in.” Tell me which one is truer. Tell me which one has actually kept me alive.

And yes, I laughed when Netflix tried to make horror movies about demons — Hollywood demons are jokes, red latex faces, cheap jump scares. Our Jnoun are not entertainment, they are everywhere.

At the lilas, when the drums rolled like a heartbeat, women screamed and laughed at the same time, whipping their hair around, and I could feel the jinn in them. I saw a woman’s blood rise from her mouth to her forehead as she smiled at me, her pupils wide and fixed in a way that didn’t belong to her. Another woman let hot candle wax drip onto her arms when Mimoun came in. The drops burned her skin, and she didn’t flinch. She just smiled, like it wasn’t hers. That’s why we never build a house without slaughtering a sheep first. That’s why the hammam is not just steam but exorcism, why wells are never innocent but black-eyed mouths swallowing children whole.

When I was little, they said a girl down the street was taken. Taken meaning her body was still here but her eyes were not, her laugh was too wide, her hands shook with a rhythm nobody taught her. And everyone knew it was Jnoun. They didn’t call psychiatrists, they called fqihs with incense and verses. I learned early that sanity itself was fragile, that possession was always waiting.

Possession was the nightmare we all carried. Not Hollywood spinning heads, not priests with crosses — no, ours was quieter and more brutal. A girl speaking in voices not her own. A boy refusing food, saying it was poisoned by unseen hands. Families whispering about how a child became “strange” after playing near a well. And what could you do? Hospitals had no cure for djinn. You needed incense, verses, salted water, a fqih with steady lungs to recite until the voice broke and the body returned.

I remember weddings where the music grew too wild, the drumming too heavy, and someone would whisper: “Careful, they like to dance too.” The night would tilt then, everyone suddenly aware that we were not the only guests. Even joy was never safe from them.

But there was also respect. Not just fear. Jnoun were terrifying, yes, but they were also neighbors. Some stories said they had families just like ours, markets hidden inside forests, palaces made of fire. Children asked: do djinn go to school? Do they pray? Do they fall in love? The adults never answered clearly. They smiled in a way that said: stop asking, some knowledge is dangerous.

When I think of my childhood, I realize I was raised not just by family, but by rules of the unseen. They shaped how I moved, how I ate, how I slept. They taught me caution, humility, and awe. Fear was not just fear — it was education. We learned that the world is never only what it seems. That every action ripples into another realm. That arrogance is punished, respect is rewarded.

Not all Jnoun were enemies. Some were said to protect. Some were bound to saints, to shrines, to holy places. Pilgrims carried offerings — candles, bread, coins — to appease the unseen. Shrines across Morocco are thick with this double devotion: part to God, part to those who live alongside God’s creation. Colonial maps marked shrines as “superstition centers,” but what did they know? They couldn’t see the other half of the city glowing at night.

There was also a strange intimacy. People invoked them for love, for power, for healing. Women burned herbs to call upon them when abandoned by lovers. Men sought them for strength, bargaining in the dark with promises and offerings. Entire traditions of music — Gnawa, Aissawa — grew out of this negotiation, this rhythm of summoning and soothing, of dancing until bodies opened like doors. Europeans came and filmed it, called it “trance music,” as if it were just art, as if it wasn’t a covenant with the unseen.

Colonialism reached for our language, our money, our borders, but it never touched the air above our heads, the shadows in the corners, the invisible crowds moving through streets and homes. The Jnoun survived. Our rules survived. And when someone heard footsteps in an empty room, rationalism shattered like glass on stone.

The French came with books, rulers, charts and microscopes, with a promise that logic could replace fear. Schools lined with desks, classrooms where the walls whispered Voltaire and Rousseau, where children were taught to think in diagrams and to ignore what their mothers murmured at the thresholds. Science was their armor, secularism their weapon, a quiet invasion meant to make us doubt what we had lived with for centuries. They built laboratories in Rabat and Casablanca, and somewhere in those white-walled rooms, they imagined we would forget the warnings about thresholds, the rules whispered over water, the teeth of the wells. And yet. Teachers still avoided marking exams alone at night. Doctors still whispered Quranic verses over the mouths of sick children. Mothers tucked threads and coins and amulets into pockets, into sleeves, into the corners of the home.

Sometimes I think Morocco is a country inside a country. The daylight Morocco, with its cafes and scooters and protests and exams; and the night Morocco, where shadows breathe, where graves glow, where the wind itself is heavy with whispers. And sometimes I think: maybe the djinn are the truest archive of us. They hold what textbooks erased. They guard the stories the French tried to scrub. You can outlaw Amazigh in classrooms, but you cannot outlaw the shiver people feel when they pass an abandoned lot at night. You cannot outlaw the silence that falls when someone starts telling a jinn story after midnight. That silence is resistance, that silence is memory.

Even today, Morocco hums with tension. We scroll TikTok with one hand while clutching threads around our wrists with the other. We study chemistry and memorize formulas, but we don’t whistle after dark. We learn English grammar, but nails stay uncut at night. Some people laugh at the old ways, call them superstition, call them backwards, and others reject the new ways, scoff at screens and satellites and clocks. All of it exists at once. It is messy, loud, stubborn, and alive.

This is not backwardness, not a contradiction meant to be solved — it is multiplicity. Morocco is the push and the pull, the friction, the clash of worlds vibrating in the same street. Morocco is satellite dishes blinking above salt circles, exam papers weighed down by incense smoke, Wi-Fi signals tangled with whispered prayers. Morocco is the ordinary brushing up against the impossible, the modern sparring with the unseen, and the living learning to navigate both at once.

And maybe this is why Morocco feels eternal. Dynasties rise, borders shift, empires collapse, but the djinn remain.

Even today, when someone feels a presence, they reach for keys, for a knife, for anything sharp. Presence is knowing that every step, every word, every careless tilt of a head resonates in a room you cannot see, that the world you walk through is listening and remembering. Presence is hearing the drumbeats in a street at midnight and knowing they are calling for more than feet; it is smelling incense in a courtyard and realizing it carries whispers older than any textbook. It is living awake inside two worlds at once — the one you touch, and the one that touches you back. To be present is to honor both, to walk lightly but aware, to know that fear and reverence are strands of the same pulse, and that everything ordinary hums with the memory of the invisible.

Sometimes I think this belief is Morocco’s deepest philosophy: the certainty that life is layered, that reality is porous, that we are not alone.

And so when outsiders ask me what Morocco is, I want to tell them: Morocco is not couscous, not camels, not sunsets. Morocco is salt at the threshold, iron in the pocket, shoes flipped the right way. Morocco is the hush after midnight, the refusal to whistle, the way our grandmothers warned us without explanation. Morocco is a country that knows too much to laugh at the unseen.

Maybe this is why I still hesitate before mirrors. Maybe this is why I never sing in the shower. Maybe this is why, no matter how modern the city looks, I know there is another city breathing just beneath it. Because Morocco is not one country. It is two. And the second one — the djinn’s Morocco —will outlive us all.

The Art of the British Greeting Card: A Tradition of Thoughtful Expression

Think greeting cards are just folded bits of paper? Think again! This beloved British tradition carries far more social significance than you might expect. This quick, light-hearted read explores the history of cards as a form of Maussian gift exchange, before delving into their contemporary role in pop-culture and issues of queer representation.

By Emma Lidzey

In Britain, greeting cards are sometimes thought of as the glue that holds us together, our very own Kula Ring (Malinowski 1922). While the rise of technology has swapped writing love letters with sending your partner a TikTok of cute cats, the phenomenon of greeting cards has not died! Fascinated by Cards' power to bring people together through an artistic medium, I was inspired to write this article, in which I will delve into the British history of cards and their social significance. I will examine what card designs can tell us about how pop culture and the intimate are intertwined, as well as how diversity becomes represented.

I first realized Britain’s inherent attachment to greeting cards when I lived in Barcelona, after having visited my girlfriend’s Iaia (grandmother) to learn to make Paella. When I told her I was going to give her grandmother a card to thank her for the fantastic experience, my idea instantly got shut down. I was told it was not a thing there, completely absent from the local culture. I could not fathom it. From then on, the absence of cards became more obvious to me. I looked to see if they appeared where I expected. Outside, there were no card shops like the ones you find on many British high streets. At Christmas, no cards were exchanged, but only presents with names scribbled on the wrapping. This lack of card exchange was so different from my home in Britain, where every Christmas, my parents would spend hours writing cards to send to old friends and family dotted around the country. When visiting a friend’s house, you could hardly ever miss the array of cards received proudly on display.

This led me to wonder where this culture of card giving in Britain came from. Central to the history of this tradition was the invention of the Uniform Penny Post in the 1840s. This system allowed people to send letters anywhere in the country for just one penny! The ease and cheapness of this system made sending letters much more accessible, therefore facilitating the circulation of cards. This card exchange is an example of Marcel Mauss’ (1990[1925]) gift theory . Famously, Mauss revealed how the act of gift giving was in no means neutral because it makes the receiver indebted to the giver, thus binding them in a relationship of reciprocity. This social network created by gift exchange is shown by the Kula Ring, made famous by Bronisław Malinowski (1922). The ritualized circulation of necklaces and armbands in opposite directions between islands in Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea strengthens alliances and social hierarchy between the different islands’ communities. Like the Kula ring, the circulation of greeting cards in Britain is an example of gift theory as their exchange maintains relationships across the country.

Another reciprocal aspect of the gift which helps explain the cards' social significance is what Mauss defines as its spirit. A force which must always be returned, like the Hau of the Maori taonga (treasures) returning to their origin in the forest via a reciprocated gift. This spirit can be seen in the emotional value of greeting cards: they have a seasonal design on the front and a message inside expressing sentiments for the recipient, sending love. The historical significance of cards in amorous relationships is reflected by epistolary relationships through history, like Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who communicated their love to one another through poetic letters. Even when the message is not so poetic or printed rather than handwritten, the card still embodies the spirit of care. The simple act of sending the card shows that someone cares for you enough to remember you, pick out a suitable card design for you, sign and send it for the occasion: your birthday, or a nationally celebrated day such as Father’s and Mother’s Day, Christmas or Valentine’s. As the saying goes, “it's the thought that counts”. Then, like Mauss’ gift, the spirit of care expressed in the card is expected to be returned with another card at the next special occasion.

Birthday cards

After pondering the history and significance of cards, I set off to a card shop to examine what else I could understand from further analysis of card designs. After a couple of minutes browsing, something became clear: the cards on sale were utterly general. For example, many of the cards in both birthday sections were images of cats, dogs and birds with party hats on. Such an image is quite impersonal, not tailored to any niche interests beyond the love of animals, for example. This is surely a tactic used by companies to make their products vague enough that everyone can relate to them, and therefore, increase sales. Moreover, all the cards shared the same general purpose: celebrating typical festivities like Christmas, Easter and Valentine’s. This could symbolize how cards enforce a normative temporality, dictating a general course of events which one must celebrate in their life. Therefore, the generality of cards shapes our personal lives by making us fit into impersonal societal norms.

Another example of how the general meets with the personal in greeting cards is the use of pop culture references. A selection of cards bore the faces of celebrities like RuPaul or Charli XCX, giving your loved ones their birthday wishes. They can be used to strengthen ties, for example, the Charli XCX card could prove to your friend - look! I know you like Brat! These cards combine public trends while maintaining personal relationships, showing how pop culture finds its way into personal expressions of affection. Cards’ mediation of shared representations and individual desires echoes what Karen Strassler (2010) calls “refraction”. This term describes how photographs become altered by personal narratives when popular photographic iconographies like state ID or studio photographs are used by individuals to achieve their personal desires. In effect, tying individuals into broader historical trajectories and contemporary narratives. Perhaps greeting cards tropes like celebrity designs could similarly be described as refracting pop culture for personal uses, thus intertwining the two.

Valentine’s Day cards

There was nothing particularly odd about the card selection until I turned to the Valentine’s Day cards and saw that none of the cards represented the LGBTQIA+ community. There were cards that said lovely comments like “you might just be my perfect person ever”, ones that made funny jokes about sex and genitals and pictured talking couples, but all of them were all either gender neutral or heterosexual. To my disappointment, there was not even one queer Valentine’s Day card, suggesting that although cards have survived the start of the tech era, at least in this shop, they are not up to date on diversity representation.

One reason for this lack of queer representation could be due to low demand, given that 80% of card buyers are women, mostly among the middle-aged and older-aged groups (HMG Pop Up Paper 2024; Mintel 2023), and that people aged 16 to 24 years are the most likely to identify as queer (ONS 2023). Perhaps the demographic of card readers would be less personally inclined to buy LGBT cards, and that’s why there is a lack. Indeed, the card designs which fill shops cater for this middle-aged female target audience, depicting a heteronormative temporality of getting married, moving house, having children, etc. However, I think that lack of demand is no excuse for lack of representation and its negative consequences. It erases the existence of older queer people who may want to send LGBT cards, as well as young people who would like to receive a supportive LGBT card from a relative or friend. Such erasure is very damaging for the LGBT community who already face denial of their identity from many angles. Therefore, even a little bit of representation in card shops would be a positive step towards fighting against the erasure and discrimination of queer people.

Although the market of card designs has a bit of catching up to do with issues of representation, I think that the culture of greeting cards is an overall positive phenomenon, in its capacity to link people to their loved ones and wider pop-culture through an artistic medium. I would encourage everyone to send cards, especially ones you have made yourself or bought from a small business, because it keeps us connected and the art world going round. Such an act feels a lot more personal than a text, and the effort never goes unnoticed. So go card-crazy! It will only make us all closer and put a smile on someone's face.

Bibliography

HMG Pop Up Paper (2024). A Closer Look: How Many Greeting Cards Are Sold Annually in the UK - HMG Pop Up. [online] HMG Pop Up. Available at: https://hmgpopup.com/a-closer-look-how-many-greeting-cards-are-sold-annually-in-the-uk/.

Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: an account of Native Enterprise and adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London, Routledge.

Mauss, M. (1990[1925]). The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (W.D. Halls, Trans.; 1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203407448

Mintel (2023). Less than half Brits aged under 35 buy Christmas cards. [online] Mintel. Available at: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/less-than-half-of-brits-aged-under-35-buy-christmas-cards/.

Office for National Statistics (2023). Sexual orientation: age and sex, England and Wales - Office for National Statistics. [online] ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/sexuality/articles/sexualorientationageandsexenglandandwales/census2021.

Strassler, K. (2010) Refracted visions: Popular photography and national modernity in Java. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

How Could You Carry Out Anthropological Studies in a Fabricated Country?

How can the fictional country of Leithanien in Arknights serve as an imagined "West" from an Eastern perspective? Analyzing the narrative of Zwilingtürme im Herbst highlights how cultural imagination, personhood, and gendered interpretations shape perceptions of history, identity, and alterity in digital spaces.

By Sihan (Coco) Yang

I still remember the day when I saw a post stating: ‘Why are studies on Europeans from other parts of the world are rarely seen’.

To me, my curiosity towards the ‘Other’ came from Europe - and in that I do not suggest that there is an essentialized and singular European culture vibe. In the past years of my life, I have been engaging with many forms of expressing the fault term of Europe in literature, comics, pictures and games. Arknights, a mobile game released in China in 2019 profoundly influenced me, where my mistaken sense and de-romanticization intersects at a time when I am drowning to Anthropology.

In this piece, I will study a fabricated country——Leithanien in Arknights stories. By fabrication, I mean an entirely fictional country designed for the game’s narrative, worldbuilding, and gameplay. These countries often allow their developers to craft unique settings, political systems. I will also refer to a specific story piece—Zwilingtürme im Herbst.

The birth of Zwilingtürme im Herbst, I argue, is interactive. Its narrative is shaped not merely by the developers of Arknights but the gamers. The story centres on a riot that breaks out in Zwilingtürme, the capital city of Leithanien, over the attempt of the resurrection of the former ruler Herkunftshorn [1] by his supporters on a national day celebration to reveal the country’s past. Among what has been told in the story, Leithanien’s past is unrevealed since 2019 and what gamers having been leaving comments on what they are looking forward to seeing in Arknights in Weibo (Chinese social media, similar to Twitter) and Bilibili (Chinese video website, similar to YouTube) where Arknights official account releases new notices. So, this piece of story does not only include the step of world-building but replying and fulfilling gamers’ curiosity and speculation of how the story of Leithien would progress. The developers’ team thus becomes an ambiguous entity—deliberately opaque—because the storytelling process in games is designed to meet diverse commercial and creative demands rather than reflect an individual creator’s perspective. This opaqueness blurs the boundaries of authorship, making it difficult for gamers to attribute the narrative or its moral intentions to a singular person or voice.

First and foremost, I argue that Zwilingtürme im Herbst offers a possibility of seeing ‘West’ from an Eastern point of view through fetishization of history. Put narratively, through NGA discussion panel, a fan website of ACG works, gamers have acknowledged that the geographical area of the Austrio-Hungarian Empire serves as the inspiration of ‘Leithanien’, and its name consists of ‘Cisleithania’ and ‘Transleithania’ (two parts of territory of the Austrio-Hungarian Empire). Leithanien has a feudal system with dual emperors and nine electors (Küfursten), which references the electoral system in the Holy Roman Empire, where the emperor was elected through the decision of seven electors. Leithanien is rich and renowned in poetry, academia and music which dominate citizens’ lives and politics. It is notably the case that on their national day, people bring their personal instruments to play the national anthem (Güldenesgesatz) together in Zwilingtürme. These cultural and historical elements, both novel and distant from the ‘Chinese’ yet ‘modern’ realities of their everyday lives, captivated Arknights authors and gamers alike, shaping both their creative expression and reception of the game’s narrative. Such fetishization could perhaps be related to recent Melody Li’s idea that the portrayal of the West by the Eastern Bloc ‘re-orientation and re-definition of these geographical locales and relationships’ and resists the ‘traditional Self-Other dichotomy set up by Orientalists’(Li, 2021: 179). However, much like the selective interpretation of ‘Europe’ we see in Arknights, we must question which ‘West’ they actually perceive? Does the creation of imagined and fabricated countries serve to reify imagination, and if so, can imagination itself be classified as reality when the West is perceived through an incorrect and biased lens?

Lanscape of Zwilingtürme

If Zwilingtürme im Herbst is seen as an alternative digital reality of Austria and Germany, I would say it learns ‘much about the framework of their society’: its history, broad political systems and even stereotypes I have just discussed (Malinowski, 1921: 13). While to create a ‘digital copy’ of a real place is extremely hard, the design idea of Leithanien primarily relies on aesthetic and symbolic elements rather than engaging deeply with the complexities and diversity of people of the regions it draws inspiration from. Instead, the ‘collectivism’ the story shows could be a means of exploring some gamers’ desired alternative notions of personhood. I argue Yan’s argument on Chinese personhood permeates through the story. Yan emphasizes, the primary guiding principle of Chinese personhood is to ‘mutually recognise and prioritise the other party’s needs and feelings in social interactions.’ (Yan, 2017: 6) Contrarily, being self-centred is ‘always looked down upon as a vice.’ (Yan, 2017: 7) Several villain characters in Zwilingtürme im Herbst represent such personhood and were highly praised. The most representative one is Arturia Giallo[2], a foreign criminal seeking political protection under the Elector of Schton, who owns the ‘originium arts’[3] of amplifying people’s emotions. She is ethically polemical since she could reinforce one's negativity and even incite one's suicide intention. Such image of a villain, surprisingly, gains love from massive Arknights gamers, and they call her ‘Huainvren’ (evil woman). However, the shaping of this character lets these gamers down, as the authors explain that her aim was to release the bondage created by rationalism and social restrictions inside people’s hearts to create a world where people could feel and empathise with each other. Gamers are looking forward to a selfish, evil image of Arturia with pathetic passion to ‘challenge the conventional way of doing personhood’ (Yan, 2017: 11).

I argue the concept of Alterity, or the recognition of the “Other,” is central to Zwilingtürme im Herbst. The concept of alterity, as Spivak argues, is shaped by the forces of nationalism, internationalism, which create the distinctions of Otherness, where I tend to explore in Zwilingtürme im Herbst by analyzing its characters and storylines (Spavik, 2013:58). Nationalism is symbolized through the Güldenesgesatz, a music composed by the collective will of ten different regions to mark the unification of Leithanien as a nation following the invasion of Kazdel.[4] This resonates with Cohen’s idea that people become aware of their cultural and national identity when confronted with “other ways of doing things, or merely contradictions to their own culture” (Cohen, 1985:40). At the same time, internationalism in the story emerges through the character of Herkunftshorn, the former ruler of Leithanien. Despite his brutal reign, Herkunftshorn is portrayed as a unifying figure in his fight against the external threat of the Collapals, an existential danger to all of Terra.[5] Facing such a universal threat, the divisions between cultures and societies dissolve, and humanity becomes one larger “self,” erasing the importance of alterity. However, as Graeber points out, alterity remains a political principle that depends on defining who is “Other” and who is not (Grabaer, 2015:34). This dynamic interplay between alterity and unity reflects on the relationship between personhood and alterity in the story piece. While Herkunftshorn’s struggle against the Collapals symbolizes a collective self-transcendence, it also erases individual and cultural personhood by subordinating them to a grand narrative of survival. In this sense, Zwilingtürme im Herbst raises critical questions about how national and global identities shape personhood, and whether the erasure of alterity in moments of collective unity undermines the recognition of diverse individual and cultural expressions.

Arturia

Herkunftshorn

Yet among the gamers, I argue the ignorance of female gamers’ demands as Arknights developers often oppresses ‘multiple realities’ in terms of gender with the masculine laud of ‘culture’ as justification of Herkunftshorn’s polemical action. According to Ortner, ‘culture’ is gendered and refers to men’s assertion of ‘creativity externally, artificially, through the medium of technology and symbols.’ (Ortner, 1972:14) Before Zwilingtürme im Herbst is released, the image of Herkunftshorn is incomplete, the only thing known is that his brutal rule caused millions of deaths among Leithanien people as he used Oripathy[6] sufferers as ‘fuel’ to explore and gain power, but his aim of fighting against Collapals[7] was not explained during that time. As I noticed, people attracted to and obsessed with the early-stage character building of Herkunftshorn were reportedly mostly female. After revealing Herkunftshorn’s motivation of ‘being immoral’, a large part of the female gamers was disillusioned, they complained how they were disappointed by a ‘Bing’ (a buzzword means leaving an unsanwered question hanging) in QQ group chats where I was a member. While many of the ‘worshippers’ of Herkunftshorn in Arknights community were male and they call him the ‘Qin Shi Huang (the first emperor of the the first unified empire Qin in Chinese history) of Terra’ by analogizing his struggle between ‘Great Deeds’ and brutality to that of Qin Shi Huang. By this, Gamers claim that although these two emperors caused significant casualties and suffering among civilians, their actions are seen as “great” because they are framed as necessary sacrifices for the continuity of society. This perspective arises from a worldview where violence is perceived as the default mechanism for achieving justice and maintaining order for the greater good of humanity.

In the end, by crafting Leithanien as an imagined ‘West’ from an Eastern perspective, Arknights invites both developers and gamers to engage with fetishization, reinterpretation, and selective reconstruction of history. These dynamics blur the line between reality and imagination, challenging the traditional anthropological concept of studying only the ‘real.’ While the reception of characters like Herkunftshorn and Arturia Giallo illuminates how diverse perceptions of personhood, rooted in cultural ideals. These tensions are further shaped by gendered interpretations, where male and female gamers’ contrasting views reveal deeper dynamics of power. Zwilingtürme im Herbst underscores the value of examining digital and fictional worlds anthropologically. These places, though fabricated, create useful insights into cultural imagination and identity formation. By engaging with such worlds, we are inspired that the boundaries between the real and the imagined are fluid, providing endless opportunities for future anthropological inquiries.

Bibliography

Cohen, A. P. 2015. The symbolic construction of community. London: Routledge.

Gabriel, S. & B. Wilson 2021. Orientalism and reverse orientalism in literature and film: Beyond East and West. London; New York: Routledge, Taylor et Francis Group.

Graeber, D. 2015. Radical alterity is just another way of saying “reality”. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 5, 1–41.

Malinowski, B. 1964. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. New York.

Ortner, S. B. 1972. Is female to male as nature is to culture? Feminist Studies 1, 5.

Spavik, C. 2013. Who claims alterity? An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization 57–72.

Yan, Y. 2017. Doing personhood in Chinese culture. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 35, 1–17.

[1] Herkunftshorn is the former ruler of Leithanien, a controversial and authoritarian figure who sought to unify the nation through absolute power and arcane mastery, ultimately overthrown and killed due to his brutal reign, yet whose lingering influence continues to shape Leithanien’s political struggles.

[2] Arturia Giallo is a foreign criminal (from Laterano) seeking political asylum under the Elector of Schton, possessing the powerful Originium Art of amplifying people’s emotions, making her an ethically controversial figure capable of intensifying negativity and even inciting self-destruction.

[3] Originium in Arknights is a mysterious mineral originating from Catastrophes, serving as both a powerful energy source and the cause of Oripathy, while Originium Arts refers to the supernatural abilities harnessed through its manipulation, akin to magic but requiring innate aptitude or technological assistance.

[4] Kazdel, historically Teekaz, is a Terran country that once located around the region which encompasses the modern-day Bleached Wasteland but now being a miniature city-state in the wilderness bordering Siracusa, Ursus, and Yan.

[5] Terra is what the ‘world’ is called in Arknights worldview, a post-apocalyptic, technologically and magically advanced world plagued by catastrophic natural disasters and a highly contagious mineral-based disease called Oripathy, where various nations, inspired by real-world cultures, struggle for survival, power, and control.

[6] Oripathy is a terminal and highly stigmatized disease caused by prolonged exposure to Originium, crystallizing within the body and granting infected individuals unique abilities while also gradually leading to their inevitable death.

[7] Collapals are mysterious and existential threats to Terra with unclear origin.

I Will Raise You Pillars

An emotive poem borne of reflections on Palestinian martyrdom while walking through the Glasgow Necropolis

by Sarah Ali

Oh mighty and tender siblings

You who hold each other beneath the rubble

Who will erect pillars in your name?

When they pile you underground

Wrapped tightly in bright blue body bags

Then destroy every record of your peoplehood?

You whose graves remain unmarked

Whose tombstones, too, they will reduce to dust

No soft and downy earth to cushion your resting place

No fresh grass to sprout from your body

Just blood to dampen the sand

When will the moss be granted liberty

To grow across your epitaph

Or the ivy to turn yellow, then amber, then

Brown?

I dream of the day your gravestone grows so

Weathered your name becomes illegible

When the only force wiping away your

Existence is time

And sun

And wind

And rain

I will raise you pillars. I raise them every day.

I will plant you greenery and flowers. Water

Them with every breath

I will honour your martyrs and I will embrace,

Embrace, embrace the living. Like my own. My

Own.

I wrote this at the top of Glasgow Necropolis (from the Greek ‘nekros’, dead person, and ‘polis’, city), a beautiful Victorian cemetery in Glasgow where over 50,000 people are buried. It’s one of the few cemeteries that keep a record of the professions, sex, and causes of death of those buried in it. As I walked among the intricately sculpted, centuries-preserved gravestones, the images I haven’t stopped seeing since October of martyred Palestinians, buried under rubble or dumped unceremoniously in mass graves, wouldn’t leave my mind. This poem is an effort to honour those Palestinians, and my commitment not to let their memory fade.

Christmas in the Anthropocene

A poem on Christmas in the Anthropocene, from anomalous climate conditions, to the Capitalist condition of Christmas, to the genocide waged on Palestine.

By Carli Jacobsen

It’s raining in Scandinavia, and it’s warm,

I reminisce the harsh and cold droplets on my skin.

Even more, I miss the snow.

Three Yule’s ago, the lake froze over,

and i bought a pair of ice skates from an old man in the newspaper.

Nevermind, that was in March, actually.

They predict a wind storm soon,

so I walk every day at this lake.

Some days, you can see auroras,

but it should be too far south for that.

Most days, there are too many clouds

clouded judgement, clouded thoughts,

They’re only hoping our holiday gifts arrive in time

from straits that only hear bombs, only see smoke.

The light is taken at three, I am guided by gold tinsel hanging on forest trees

and mushrooms, still lush on December seventeen.

like it’s a Christmas in the Anthropocene.

or is it a Capitalocene? I don’t seem to recall the difference

as I stroll through the market and I think “sustainable Christmas?”

where crayfish* invade the fish monger stalls

at astonishing prices

for my wallet, and for the planet.

And this Christmas, we listen to music,

War is over? I think twice;

of the ard asli [the original land], **

about a birth of a boy in Bethlehem

trapped under the rubble,

of the Christmas shit I want, not need

of the BBC instead of Love,

actually.

*crayfish is an invasive species in Denmark - reference to prominent debate about the ethics of killing off invasive species.

‘Anerkend Palelaestina’ which in Danish means ‘recognise Palestine’ on the walls of Copenhaghen. Picture taken by author

This is a rebel song: an obituary of Sinead O'Connor

An obituary of Sinead O’Connor, in recent times also known as Shuhada’ Sadaqat. The music of the Irish singer recently passed away has still a lot to tell us, especially at the present moment, about resistance to domination and its abuses.

Cover picture: Shuhada’ Sadaqat by Ellius Grace for the New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/18/arts/music/sinead-oconnor-rememberings.html

By Carli Jacobsen

Sinead O’Connor authentically uses her music to encapsulate Irish, personal, and international struggle. Nothing can get past the lyrics of her music: she is always so sudden to express an often-taboo truth of controversies, but nonetheless is still held as the moral compass of Ireland, even after her death in late July. Her ruthlessness is best known from the moment she tore up a photograph of Pope Jean Paul II on a Saturday night live in 1992 to address child abuse in the catholic church. The outcries from the public for her provocative conversations never stood in the way of using her position as an artist to create and remind the world of resistance in Ireland. She boycotted the Grammy’s, refused to participate in the US national anthem, and whole heartedly used her screen-time to express her devotion for the refugees of Ireland.

She embodied Irish struggle and resistance, encouraging other Irish people to never turn a cheek to the injustices under Irish leadership, particularly in relation to the Catholic church, to which she was known as in Irish icon of resistance. She became a priest in Belfast, despite the Vatican’s rejection of women in such positions, but continued to bless and perform her duties to God and the people of Ireland as a religious activist that advocated for transparency and inclusivity in the Irish Catholic church, sharing her own experiences of queerness, bi-polar disorder, and abuse from her mother. Her experiences were shared as a reminder of the genocide against Ireland, and its long-term effects on mental health that she addresses in her songs.

From her album Universal Mother, Famine exposes the harsh treatment of the Irish people, addressing propaganda and the false narrative of the death of 1 million Irish people. Through listening to her albums in order of their creation, you embark on a journey of Sinead’s spiritual growth and become embraced in the inconsistencies of her identity through her music in parallel with her struggles of healing and of emotional peace. These inconsistencies are the utmost human cultivations of the self as written through song, but these inconsistencies are constantly made sense of through her ongoing radical critique of colonial and capitalist establishments. Her music tells a story of personal growth from a young and remaking Sinead, to a vengeful and will powered Shuhada’ Sadaqat, her name after converting to Islam in 2018, when she reclaims craziness and revitalises her musical talents that have only ever exacerbated love for the marginalised and shame for those in power that attempt to crumble resistance and revolution.

Sinead O’Connor at the Grotto in Lourdes, France, a Christian pilgrimage site (Michael Crabtree/PA):

We think of both Shuhada’ and Sinead as entangled identities that show unity in resistance, particularly between Ireland and Palestine. Ireland, as one of the few member states supporting a ceasefire regarding the Palestinian genocide, and as one of the only long-standing advocates for the liberation of Palestine since the Nakba in 1948. Both Ireland and Palestine have experienced genocide, oppression, censorship, and the stripping of resources as a human right, and these struggles see unity between both groups. Their flags are used interchangeably as symbols of resistance against struggle.

Shahuda, even before her conversion to Islam, stood up for the Palestinian liberation. In 1997, she wrote a letter to Israeli defence minister Ben Gvir to condemn the Palestinian occupation and condemn his actions as a leader, after he sent death threats to her and her band. More profoundly, her songs rewrite the Irish occupation. Through music, she has curated a new Irish history that expresses emotions of mourning, anger and hope, like the power of Palestinian music by musicians like Khamal Khalil, who plays with dawla to negotiate the violent power of occupation and complicity of both Israel and nearby Arab states and was arrested after his songs were played in the streets amongst activists and shabab, and curators such as Mo’min Swaitat’s Majazz Project, who has compiled tapes and vinyl's of revolutionary resistance music and cinema, mostly from Jenin in the West Bank.

The 11/11 March for Palestine in London, where over 800,000 people protested, making it one of the largest demonstrations in British History. Photo taken by author.

Through the contemporary work of Mo’min’s project, we can learn together about the importance of music to navigate violence and exile across political context, from Palestine to Sudan to Kashmir to the Congo. While Sinead’s music was not around to actively resist the Irish occupation, it tells a story today of a reclaiming of narrative that has previously written a famine ridden, barren, terrorist Ireland. Listening to resistance music today reminds us of ongoing political violence where revolution is simmering, using the poetics of national and cultural pride to challenge the dominant narratives that mislead us away from the streets on which we protest.

Extracted from my favourite song of hers, Famine, I share these lyrics, but recommend listening to her music remembering her influence both in Ireland, and in Palestine, especially in the context of the current political crisis that we all should be attentive to learn and understand.

And if there is ever gonna be healing

There has to be remembering

And then grieving

So that there can be forgiving

There has to be knowledge and understanding.

A Walking Ethno-poem of Soho's Streets

The realisation that what once felt confusing has now become mundane, habitual. I wrote this poem whilst walking around Soho one day when I forgot my headphones, so I had more of a chance to observe everything on a route I take often.

A poem by Finola Stowe

Forgot my headphones so street music is more appealing

The unrecognisable instrument

that somehow gets you from A to B

I walk with aim

There’s purpose on these roads.

My route governed by “when I went here”s and “last time”s

Past times guide me and I never thought i’d be familiar

with a Soho street

Person brushes or crashes past me and I say something kind of mean in my head

bu remember that self development girl on YouTube who told me not to think

ill of other people

Peaceful

is literally nothing in this city.

Trippy lights and displays make up the scenery and I’m overwhelmed but

they’re explaining why I should buy this and that and yes,

I agree,

I should buy it

Halt my walk to find it

Consume it.

There’s girls on the street and gum on the floor

Worlds upon worlds of un-ironed business attire, books carried in arms to feign intellect

and calculated hairstyles whilst I take extra steps to consciously avoid

these complex people

of Soho’s streets

Things you do on a walk alone are fluid and unforgettable/

A time of its own

Tracing how I’ve grown

I’ve been walking here for two years

but I still look for the same clues

on the same routes

I traversed back then and

thank

the racket of soho streets for

guiding me.

The Book of Mormon - on the boundaries of political incorrectness

A review of the play ‘The Book of Mormon’

Photo credits: show’s poster - https://www.broadwayinlondon.com/the-book-of-mormon

By Pia Tasso

Blasphemous, racist, undeniably offensive. In a society that seems to be tending towards a hyper-vigilance to political correctness, how is it that a show that essentially gives the middle finger to the Mormon Church continues to be so widely acclaimed?

Winner of 9 Tony Awards including Best Musical, The Book of Mormon, written by Trey Parker, Robert Lopez, and Matt Stone has grossed over 1 billion dollars internationally and continues to be one of the most enduring Broadway plays. From John Stewart to Oprah Winfrey, the show has been overwhelmingly well received, so much so it would nearly seem out of place to put in question the legitimacy of its jokes and overall message.

Loosely, the show follows two missionary Mormons, Elder Price and Elder Cunningham – the former a bright attractive man and the latter a gullible man who adulates the former. Sent to Uganda on a missionary operation, they endeavour to convert the local population to the Church of Latter Day Saints. Living in precarious, dirty houses that are depicted to be Ugandan ones, they initially fail to convert the locals. Discouraged by such an outcome, they eventually start lying – making up stories to convince the people that Mormonism is relevant to them all. This eventually leads to their realisation of the metaphorical nature of religious accounts and encourages them in the spread of their new religion across Africa.

On paper, one would think that a show simultaneously mocking a religious minority and the colonised populations it has converted would spark some controversy. Perhaps the key to understanding the reason for the show’s surprisingly socially acceptable nature lies in the choice of actors to embody this synopsis – namely the Mormons and Ugandans.

One of the catchiest lines of the show might just be ‘I am a Mormon, and Mormon just believes’, evidently mocking the Mormons’ naïve credulity and lack of pragmatism. But could the same joke not be made just about any other religion? ‘Religion’, and by extension faith, arguably necessitate a degree of non-entirely empirically rational belief, in the contemporary Western understandings of science and factualness. In other words, isn’t it the very premise of a religion to ‘just believe’? It could be argued that the same statement could be applied to nearly any other religion – or in fact to supposedly ‘non-religious’ entities too. This might suggest that Mormons are the scapegoats through which to mock ‘faith’. But because 'faith' is so intrinsically human, perhaps we should consider the idea that our laughs also vent our own insecurities regarding ‘God’ and ‘religion’ in the broad understanding of the terms.

Photo credits: Julieta Cervantes - https://qcitymetro.com/2018/07/27/time-that-a-black-person-reviewed-the-book-of-mormon/

This recognition of the show’s broader underlying themes begs for a parallel with other religious groups. Would the show have been equally acclaimed if it treated Islam, and depicted Muslims as naïve worshipers who ‘just believe’? Or would it for the same matter be guiltlessly enjoyed if it poked fun at the Jewish community’s blind faith, considering their complicated history? Though this line in itself bears little importance, such analogies open the door to the reconsideration of the jokes that flow through the play, starting from its very title. Just consider the show being called ‘The Koran’.

Though these are only abstract speculations, my point is to denounce the bias that is intrinsic to our tolerance of political incorrectness, revealed through the boundaries of socially acceptable humour. The metrics by which we abide humorously are defined by an unspoken script, and the show is a contemporary example of those implicit preconceptions. This is not to question the legitimacy of the authors to mock the Mormons – their humour is somewhat beyond their control, predetermined by social norms and values. But precisely because of that fact, irony powerfully informs our understanding of the underlying socio-political dynamics that permeate our world.

Though the show may in part be ‘funny’ because it took an easy scapegoat to mock religion, we must not forget the other party in the show – the Ugandans. The script is flooded with racist jokes, yet it seems no one gets offended. To give one example, one of the running gags is a man explaining how he now has sex with frogs instead of babies to deliver him from his aids. Another character also complains that he has maggots in the scrotum, but they cannot get a doctor, because he is the doctor…LOL! In theory, those jokes mock the missionary’s conception of Uganda and Africa and thus serve more as a criticism of Western prejudices. But is that really so? The ironic nature and setting in which those statements are embedded make them acceptable. Irony is by definition ‘not true’, and getting offended would theoretically be a lack of humorous awareness. In this context, however, doesn’t irony serve as a façade to enjoy a good old racist joke?

This opens the door to an important theoretical debate surrounding the role and boundaries of irony. Humour and satire are irrefutable pillars of freedom of speech, and constitute valuable political tools. This being said, though everything can be poked fun at theoretically, we must recognise the blatant bias in the choice of groups that embody those jokes, as well as the underlying ideas that incite us to laugh at certain jokes. The playwrights disappointingly use irony to reinforce pre-existent dominant and racist narratives when they could, and arguably should, have challenged this very status quo. Irony is therefore powerful but also dangerous and I merely want to debunk the idea that one cannot take offense because it is ‘not true!’. Perhaps the key is that we should be more introspective of the boundaries of irony as a marker of the limits of our freedom of speech and the collective moral code we tacitly abide by. The Mormons and Ugandans are just defenceless props of our ritual of moral and intellectual ablution, and our laughs a vain form of penitence.

On 'The Banshees of Inisherin'

A review of the 2022 movie by Martin McDonagh

Cover picture: a Banshee watching over Colm and Pádraic walking away from one another

By Carli Jacobsen

Martin McDonagh’s work is recognisable as a masterpiece at the first string of Colm’s violin. The film tells of the relationship between who suddenly begins to imagine a future greater than one that has Pádraic in it. Only in the final minutes of the film did I come to terms with Pádraic and Colm’s relationship to be a stab at the Irish Civil War: After endless threats by finger(s), and countless attempts from Padraic to reunite with Colm, a war between the two men begins. By the closing scene, one may have completely forgotten why exactly they were fighting in the first place.

Pádraic (Colin Farrell) on the right and Colm (Brendan Gleeson) on the left

It took a moment to decipher exactly who plays the Protestant and who plays the Catholic, yet Pádraic and Siobhan's (Kerry Condon) dedication to the Sunday mass and the Banshee, being Mrs. McCormick (Sheila Flitton), whom they host for the occasional dinner, while Colm has doubt over the oracle telling of the Banshee and struggles to identify sin in his own life during his confessions. Although this is confirmed by Pádraic’s slagging of Colm’s mispronunciation of Irish phrases and his high regard for Mozart, claiming Colm has begun to sound Anglo. And when Pádraic places the ultimatum to resolve the friendship, or burn Colm’s house at 2pm, it is a mirrored moment on the 27th June 1922 when Michael Collins' ultimatum to the four garrison to surrender before 4am. At 4:15 on the 28th June, Collins bombarded the Four courts with a pair of British field guns.

Colm’s house burning

McDonagh embarks you on a journey of brilliant orchestra, cinematic candy of rolling hills and cliffsides, and a dark humour of catholic mockery that is reminiscent of the 2016-2019 dry witted Fleabag series, produced by, written by, and starring Phoebe Waller-Bridge, who also happens to be McDonagh’s partner. The Banshees of Inisherin is a beautifully conducted period piece who’s meaning transcends in time frame, making one laugh and perhaps cry through moments of hostility, rejection and revenge that cannot be separated from the ongoings of personal battles and conflicts in contemporary politics.

The existential and the political: anthropology and Chris Killip

A reflection on the first retrospective exhibition on the work of photographer Chris Killip and its relationship with Anthropology

Cover picture credits: Chris Killip, Helen and her Hula-hoop, Seacoal Beach, Lynemouth, Northumberland, 1984

By Iacopo Nassigh

The first retrospective exhibition on the work of Chris Killip (1946-2020), a Manx photographer who has mainly worked in the North of England terminated just one week ago at the Photographers gallery, Soho. Killip’s work expresses a disenchanted gaze on the life Northerners throughout the 70s and 80s, during which the closing of factories and mines left many people without a job. However, Killip’s photographic gaze is not trying to romanticise the resistance of those who remained in the North. His photography is embedded into a deep awareness of the need of solidarity and amplification of these people’s lives, and not of pity for these marginalised groups. With this awareness, Killip spent months and years with the communities he photographed, such as the years he spent in Lynemouth, Northumberland in the early 80s staying in his van among a community of workers in an open-air coal mine by the sea.

Chris Killip, Gateshead [punks], 1986

Even if sharing the same basic experience of an anthropologist doing prolonged fieldwork it seems to me that his poetic eye was seeing something quite different from what an anthropologist normally sees. Where anthropologists see resistance to structural oppression Killip was able to see the human capacity to find relief in despair, to enjoy life as it comes despite the world burning around. His image of a girl playing with a hula hoop or the pictures he took of young punk man going crazy at a rave speak not just of people that find meaning in cultural structures, as old Geertz would put it, but people that actually enjoy themselves without caring much for a while about anything else. This existential quality of Killip’s photography is what I will carry with me other than an even stronger conviction now that things are not just suspended in cultural or political structures. Instead, if one has the eye to see this and suspend disbelief for a second, things can be appreciated for themselves, as moments of emotional explosion that maybe just a photograph can express.

Fuseli and the perceptions of womanhood

A review of ‘Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism’, an exhibition at the Courtauld gallery featuring a series of private drawings by the eccentric 18th century Swiss artist, Henry Fuseli (1741- 1825).

by Claire Ding

Last December, I was fortunate to see the work of Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), one of the most eccentric 18th century European artists, at the Courtauld gallery. The exhibition, Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism, explores notions of sexuality, gender, and womanhood, which were constantly being challenged and reshaped during the Victorian era. An array of his private drawings were displayed, foregrounding different courtesans and his wife, Sophia Fuseli, as the centre of attention. Breaking away from female stereotypes of submissiveness and maternal virtues, Fuseli’s work of the Modern Woman destabilises traditional understandings of womanhood. In my opinion, however, his reimagination ultimately does not seek to empower women and continues to confine women in archetypal roles, subjugating them to the aesthetics of an alternative, but nonetheless male, gaze.

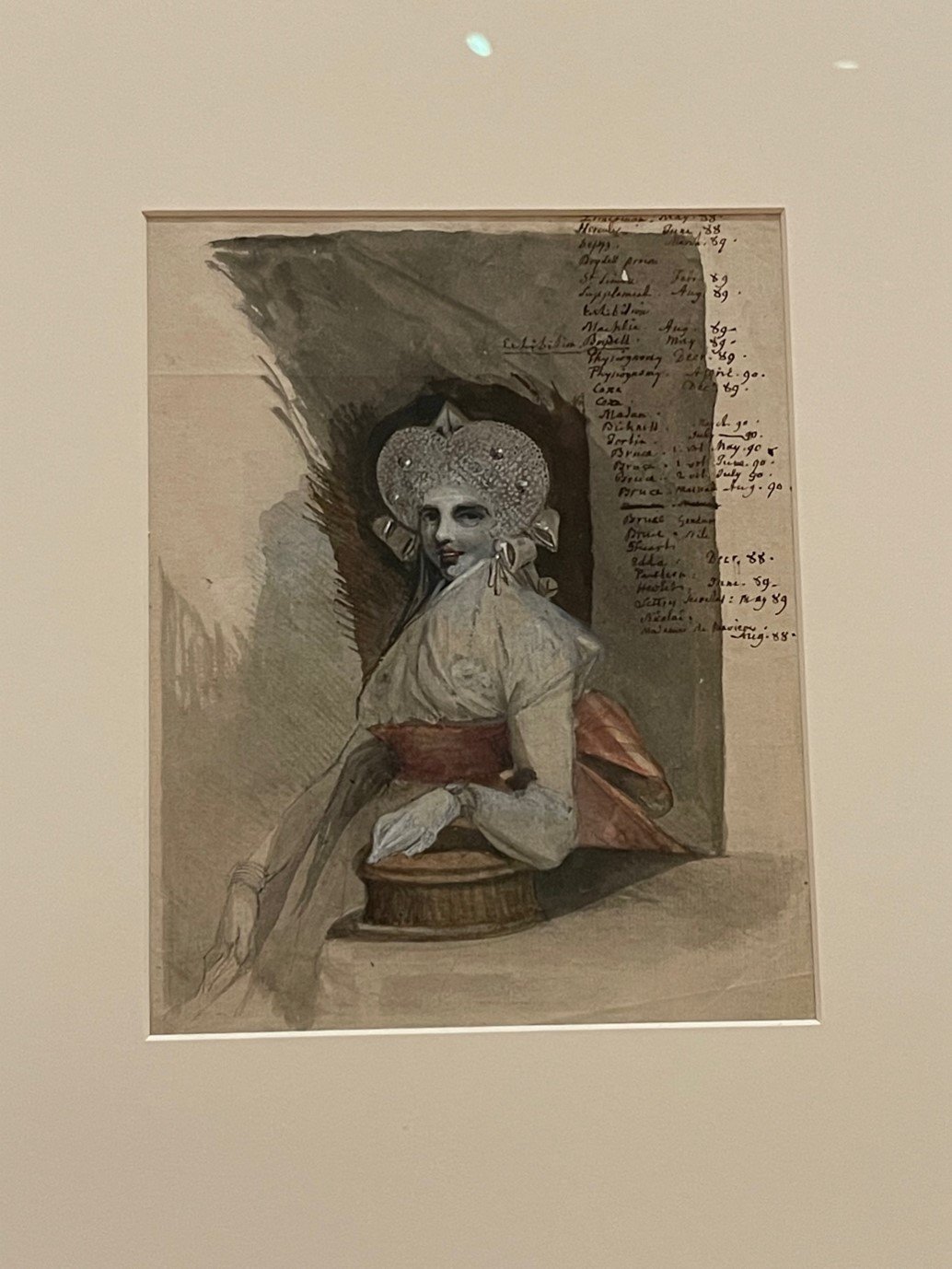

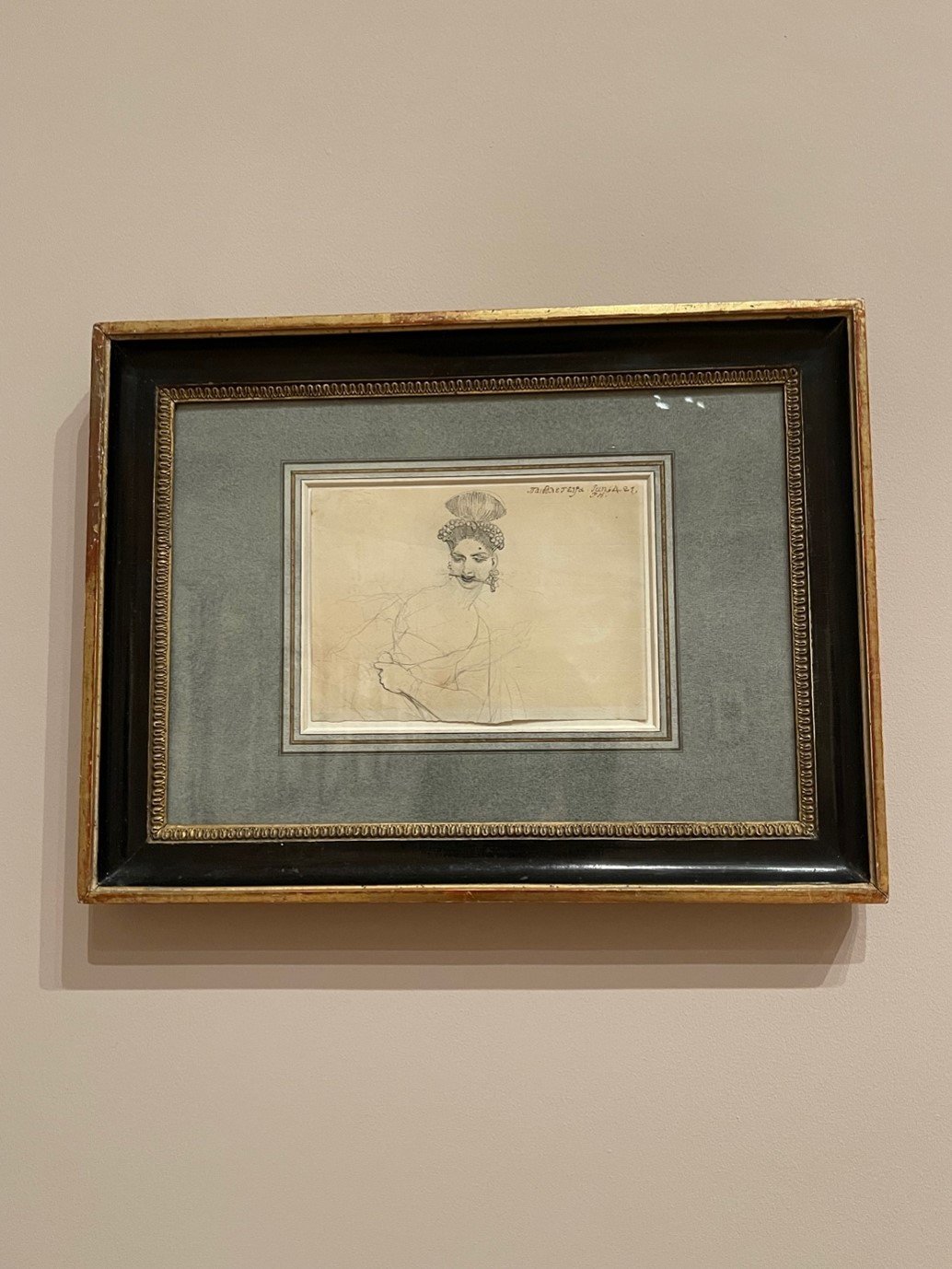

Fuseli does, however, showcase the multiplexity of womanhood by subverting female archetypes through the lense of the appearance and clothing of courtesans. In ‘Sophia Fuseli, Standing in front of a fireplace’ (1791), Fuseli casts his wife in an elaborate drapery with a complex hairstyle, reminiscent of a courtesan. This depiction is further reinforced by her pink cheeks and red lips, and green facial complexion recalling concurrent tuberculosis aesthetics. Interestingly, Fuseli situated Sophia in a domestic setting, marked by the fireplace, which is affiliated with notions of maternal love and care, creating a stark contrast with an erotic appearance associated with women of a dubious moral character and wild sexual passions. Such oppositions can also be seen in ‘Sophia Fuseli, Seated at a table’ (1790- 91). On one hand, Sophia exemplifies sexual immorality, portrayed by her seductive gaze, voluptuous lips and translucent drapery; the sewing basket next to her, on the other hand, associates her with virtuous domesticity. By doing so, Fuseli converges and distorts Victorian female archetypes of the angel in the house and the fallen woman, thus freeing perceptions of womanhood from conventional understandings.

Sophia Fuseli, Seated at a table Sophia Fuseli, Standing in front of a fireplace

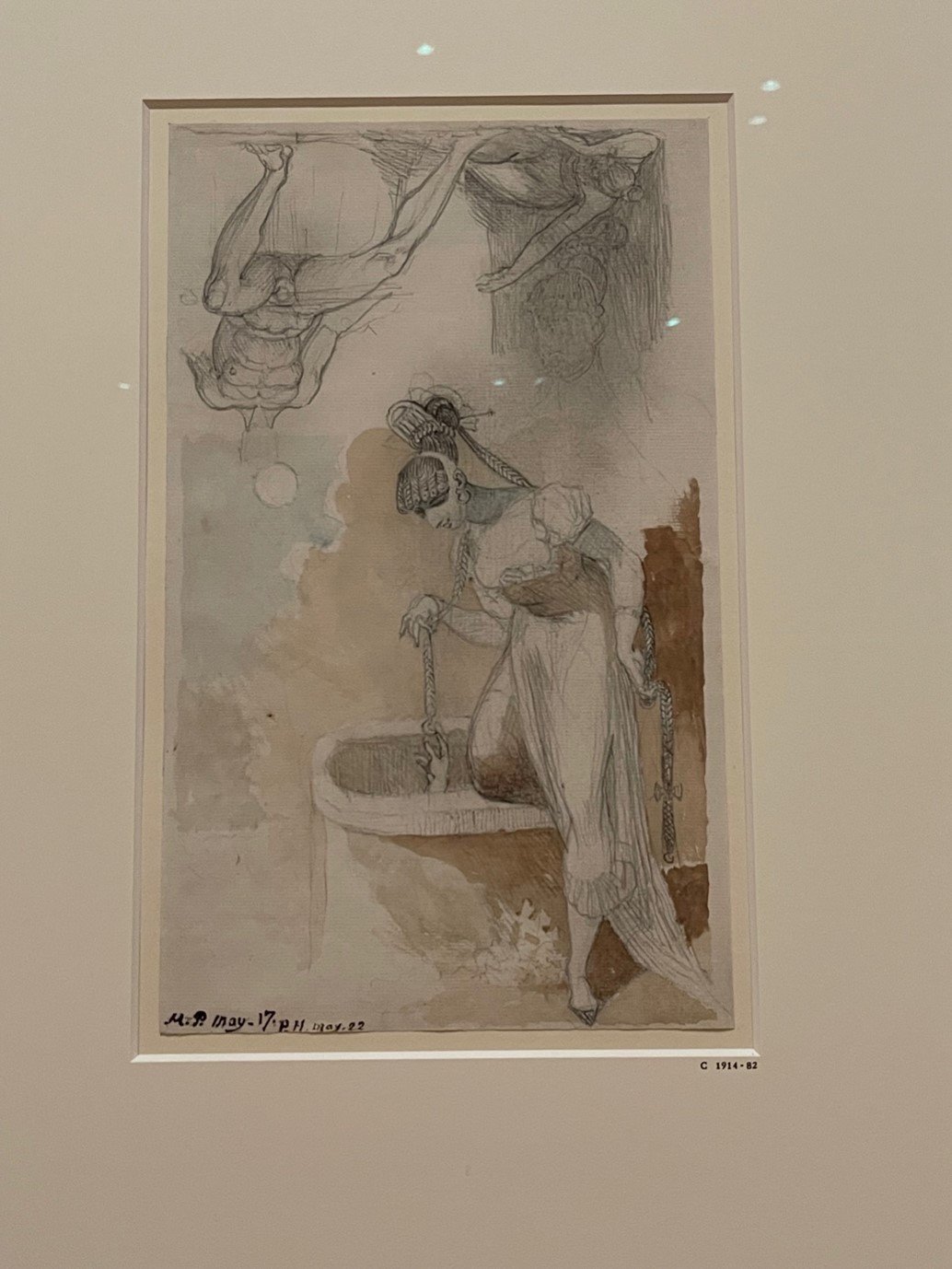

Fuseli further disrupts the perceptions of womanhood by turning women into powerful perpetrators who commit sadomasochistic acts. It has been suspected that this darker side of Fuseli’s imagination was influenced by the writings of Marquis de Sade. In ‘Paidoleteira’ (1821), the courtesan is depicted as committing infanticide using a hairpin and the drawing has a Greek inscription of ‘child murderer’. Similarly, in ‘Woman with long plaits teasing a figure trapped in a well ‘(1817), Fuseli positions the woman as powerful, not only presented by the subject matter itself but also the use of a hierarchical composition. Nevertheless, the empowerment of women in Fuseli’s can be questioned as it appears to serve and appeal to the tastes of the libertines, who likely would have been Fuseli’s clients, rather than giving genuine agency and autonomy to women. In addition, the ubiquitous male gaze not only penetrates his sadomasochistic imagination of women, but also his drawings of female fashion. A recurring motif in his work is the juxtaposition between geometric or phallic shaped hairstyles with an open, provocative display of the female body, which is particularly prominent in ‘Kallipyga’ (1790- 92).

Kallipyga Woman with long plaits teasing Paidoleteira

a figure trapped in a well

The exhibition ultimately opens a broader discussion of womanhood and who has the power to define it. Fundamentally, Fuseli as the artist, has the power to imagine and represent womanhood based on his fantasy. This, nevertheless, is a product of the broader social climate, as well as the preferences of his clients; upper-class men. Perceptions of womanhood continue to be written over by the male gaze in art, meaning that women in the drawings of Fuseli are empowered, but not dignified. Following further waves of feminism, as well as the rise of female artists in modern and contemporary art, increasingly we see perceptions of womanhood on a much more individualistic and personal basis, by women themselves. Artists such as Fuseli can be appreciated for their socially innovative nature, but should be admired whilst recognising their historical contingency.

Who's hands?

A poem by Ishani Milward-Bose.

This poem was written as a visceral reaction after witnessing the horrific labour conditions that young men and women working in the construction industry of the developing world have to withstand. It is by nature reactionary and emotive.

Who’s hands?

a poem by Ishani Milward-Bose

Who’s hands have touched this soil?

Who’s feet, bare, have laboured?

Imprinted on our landscape;

From dead skin cells,

Blood dripped from a scraped elbow,

Sweat flowed from exerting bodies,

Under the blistering sun.

A young boy carved his name into the setting cement;

A despondent attempt at recognition, or possession, or ownership.

At materialising and immortalising his part in the process;

Painstakingly scraping cement, hammering rods, welding joints,

Memories of desperation etched into the concrete.

That is all that remains marked

Of the hands that touched that soil,

The feed that laboured on,

The touch that built it up;

The monstrous grey scar in front of me.

Camera and Retrospect: or How to Annotate Life

The art of photography comes with the challenging nature of politics of representation and narratively complex entanglements. Amidst these anxieties, one must not forget to celebrate life through the lens of their camera and capture what they deem peculiar, beautiful, and thrilling. Here, I want to share three photographs representing exactly this sentiment; to photograph is to express your appreciation and awareness of those that surround you.

“Dear Readers: observe, enjoy, and capture life in any medium that satisfies your eyes and mind.”

by Nazli Adigüzel

Since I started studying anthropology, I have been thinking about my relationship with photography. Quite often, I discourage myself from pressing the shutter button, allowing thoughts about Power and Narrative to settle in. Although a healthy amount of self-reflection and an understanding of the politics of representation are crucial to consuming and appreciating visual media, one must not forget the sheer joy capturing an instance can be. For photography is to still time, materialize an interpretive reality, and visualize the narratives we construct. Here, I share a few photographs I have taken over the years. Some are mere combinations of pixels, occupying their places in my SD card, and some have undergone chemical processing in darkrooms, now stacked on top of each other in my dusty albums. Despite their textural differences, in my opinion, they all embrace the beauty and oddities of everyday life.

1. This first photograph, taken during the 2021 lockdown, is from a virtual ballet rehearsal of my sister, who was kind enough to allow me to photograph her. When Time, as we sensed it (with its schedules, alarms, and calendars), became obsolete, my sister’s online ballet classes were one-hour reminders of the fact that Tuesdays and Thursdays still existed outside of our house. Looking back at this photograph, I now understand why 19th-century Impressionists were constantly painting ballerinas— the stamina and the elegance they exude are utterly transcendental.

2. Boredom breeds creativity, some say. This is precisely what happened to me when I was having a staring contest with this Venetian mask instead of doing my calculus homework when I was 16. This mask still dares the dwellers of our living room to a staring competition, but I believe I was the only one in our household to take a photograph of it by placing a piece of fake-crystal prism in front of my lens

3. It is not every day that I am genuinely impressed by street musicians, yet I still think about this Austrian duo converting Museumsquartier in Vienna to the set of Alice in Wonderland. I took many photographs during that trip, some of which I am quite satisfied with, but this one remains my favourite because it is a simple reminder of how genuinely fun humankind can be.

In high school, my literature teacher would always tell his students to hold a pen while reading because it would encourage us to annotate. Here, I tried to choose photographs that I took before I started studying anthropology; it was a period of my life where I was truly annotating life with my camera, one eye closed and the other looking through the lens. This is mainly a reminder for me to start carrying my cameras with me, and hopefully, this can be an encouragement for you, too, dear Readers: to observe, enjoy, and capture life in any medium that satisfies your eyes and minds.

Three Sisters Soup - a First Nations recipe

An insight into First Nations cooking - recipe by Carli Jacobsen.

Photo credits: https://mcmichael.com/collection/first-nations/

by Carli Jacobsen

Three Sisters Soup (bannock beans, corn and squash) are the ‘three sisters’ in traditional ecological knowledge, originating from First Nations Peoples in the United States and Canada. The Three Sisters are usually planted together because they each aid the growth of the other. They collectively contribute to a balanced meal with different textures are flavours deriving from each ingredient. Bannock, also called fry bread, is another traditional cuisine used in savoury and sweet ways. Bannock pairs well as bread to eat with the soup, but also can made into ice cream sandwiches, or eaten plainly with tea. They can be frozen or re-baked for later use. Both these recipes are inspired by traditional recipes I found online by First Nation chefs but have been slightly altered to suit the produce available in London supermarkets. They are vegetarian but can easily be made vegan with plant based duplicates.

Three Sisters Soup (Serves 5):

Half of a butternut squash

1 large can of corn

1 can of butter beans

A generous dash of curry powder

A few curry leaves to your taste

Red pepper and salt to season

1 Vegetable broth

1/2 a white onion

4 garlic cloves

50g of butter.

Olive oil

Runny yogurt and fresh coriander/cilantro to garnish (optional)

Method:

Roast the squash and the garlic coated in olive oil for roughly 2 hours until both are soft enough to mash with a fork.

for the last 30 minutes of these in the oven, add the sweetcorn. Spread the corn out on a pan and roast in olive oil, S&P. The corn should be slightly browned/crispy.

thinly chop the white onion, and caramalise in the butter with the salt, red pepper and curry powder.

Once caramalised, add the stock cube, the butter beans, curry leaves, and slowly add the water bit by bit.

Using either a fork or a blender, puree the garlic cloves and the squash, adding it to the soup to make the broth thick and creamy. If too thick, slowly add more water. Simmer on mid-low-heat for about 10 minutes on a mid-low heat.

Within the last five minutes of simmering, add the roasted corn. This adds a little crunch, so you can individually enjoy the various textures and flavours of the Three Sisters, while being able to see how they compliment each other too!

Season to taste with S&P, and drizzle with yogurt and corriander if you like. Serve with bannock either to dip in the soup or to use for an ice-cream sandiwich dessert (or both!).

Bannock (Makes a dozen depending on preferred size):

(American cooking measurements incoming, apologies!)

3 cups of all purpose flour

2 tablespoons of baking powder

1 teaspoon of salt

1 1/2 water. Some recipes use milk.

1/4 melted butter.

If you wish to use the bannock strictly for dessert, you can add caster sugar to your taste.

A vegetable or seed oil of choice (I used sunflower).

Method:

Mix all the dry ingredients together in a large bowl, and create a cave in the middle, adding all the wet ingredients.

Using a fork, slowly bring the dry ingredients into the wet ones until you get a thick and very stick mixture that represents a thick batter.

In a large skillet, add the oil so that it fully covers the surface of the pan. Heat until hot (be careful)!

Using a spon, add large dollops of the batter to the pan, frying until golden brown on each side. It should be in the pan for about 5 minutes in total!

Allow them to cool on a paper towel to suck up excess oil. Keep adding more oil to constantly layer the pan when frying.

To use as an ice cream sandwich, slice the bannock width-ways to create 2 thin slices, spreading ice cream and fresh fruit in between. Enjoy!

Little Homes

Everyday sights, sounds, conversations, and rituals, were so important for Sarah Ali in evoking a sense of home. This is a poem they wrote when living abroad for the first time, along the icy Neretva river in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

a poem by Sarah Ali

It’s the mundane that takes me back:

sunlight glinting off turquoise peaks and swirls of the Neretva,

a raucous kitten winding between my feet,

coconut milk still fresh even out of the can.

Sunlight hits the backs of leaves and sets them alight, a sea of lime and lemon.

My Turkish- and Arabic-speaking friends sit with me and we pass around words

like we’re playing hot potato, or Chinese whispers,

Until something clicks.

Qabool, we cry; a commonality among our tongues.

Believe. Accept. Concordance.

The other night I dreamt

of a winding road back home,

one that led to my best friend’s back door.

His jasmine tree had snowed petals along the soil;

they melted into my palms and fingertips

and I woke up disoriented - the way I felt as a child,

falling asleep on the sofa and waking up in my own bed.

Note: everyday sights, sounds, conversations, and rituals have been so important for me in evoking a sense of home. This is a poem I wrote when living abroad for the first time, along the icy Neretva river in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Music at the Margins of Empire - 'Argonaut Mixes' in the spotlight

In this short piece Lucy gives us a taster of her Argonaut November Mix. ‘Liberated Woman’ by Rankin Ann is an ode to Britain’s first black-owned pirate radio show Dread Broadcast Corp as well as Ann’s later shows on BBC Radio - a national celebration of Black British music.

“Music is fundamental to human experience and encapsulates culture, struggle and communitas, and I hope each month’s mix might shed light on this widely silenced music.”

by Lucy Bernard

Each month I curate a playlist of global, fusion and protest music to accompany the newsletter. Music is fundamental to human experience and encapsulates culture, struggle and communitas, and I hope each month’s mix might shed light on this widely silenced music.

Rankin Ann – Liberated Woman: a glimpse from our monthly playlist in 'The Little Argonaut', issue 001.

Dancehall music has been seminal in British culture and black empowerment. Selecta Ranking Miss P began broadcasting on the first ever black pirate radio station 'Dread Broadcasting Corporation' in 1979. She went on to host Radio 1’s first show dedicated to reggae music ‘Culture Rock’ in 1985 and later hosted BBC Radio London’s ‘Riddim and Blues’ on Sunday nights. In parallel, Rankin Ann encapsulates this female-led integration of reggae music into mainstream British media. Her 1982 track ‘Liberated Woman’ from the album ‘A Slice of English Toast’ takes a classic dub track reminiscent of Trojan Records’ Big Youth, brought to life with Ann’s lyrics of female liberation. Reggae’s emergence in the UK was transformative and the (perhaps unlikely) fusion of punk and reggae in the late 1970s as depicted in Bob Marley’s ‘Punky Reggae Party’ and The Clash’s cover of ‘Armagideon Time’ is reflective of the anti-establishment politics of the time. On the Clash’s B-side recording at around 03.00 minutes Joe Strummer shouts “Don’t push us when we’re hot!” after apparently being asked to wrap it up. Dub-powered music is fervently passionate. Indeed, prophet Marcus Garvey prophesied that when the two sevens clash ‘injustices would be avenged’; perhaps this fusion is an ode to exactly that.

In Flight

A poem by Maya Patel

In Flight

by Maya Patel

The trouble with moving is that it brings disquiet

when you’re here, you long for there

when you’re there, you wish you were here

with each move, it’s like a part of your identity is on the move with you - constantly growing, changing, evolving

until you’re not sure what separates one part from another

until you can’t remember where you felt most rooted, most grounded, your happiest

because you know change is coming

uncertainty within uncertainty and all you want is home...

but home has multiple meanings now

and you’re in limbo until the next one reveals itself.

A view on nationalism and race at the Moosgard Ethnographic Museum

A view on nationalism and race at the Moosgard Ethnographic Museum

by Emmanuel Molding Nielsen

Situated in the bucolic hills of Aarhus bay in Denmark the Mosgaard Museum cuts a striking figure in the landscape. Its pre-history exhibition, the most prominent item currently on display, is interactive, immersive, and deeply informative. Yet, for all its laudable, and for the most part successful attempts at chronicling East Jutland’s prehistory and bringing anthropology to the lay public, the museum’s uncritical engagement with nationalism is naïve and at worst racist.

The good