Whose peace, whose history? Reflections from two museum visits in Seoul: the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum and the War Memorial of Korea

This reflection on two museum visits in Seoul, South Korea considers the notions of “peace” and “sacrifice” in different narratives of history. The intimate and confrontational War and Women’s Human Rights Museum focuses on the halmonis who suffered under Japanese military sexual slavery in WWII. Encompassing historically marginalised women’s bodies and voices and Vietnamese victims of sexual abuses perpetrated by Korean soldiers, the museum disrupts patriarchal and nationalist discourses. By contrast, the monumental War Memorial of Korea covers a broad military history of centuries of wars on the Korean peninsula, highlighting heroic values and Korea’s nationhood. Looking into diverging discourses in museum spaces and the relationship between materiality and memory, this piece reflects various ways of understanding violence, hope, peace and solidarity in the long shadow of conflict.

By Elise Lee

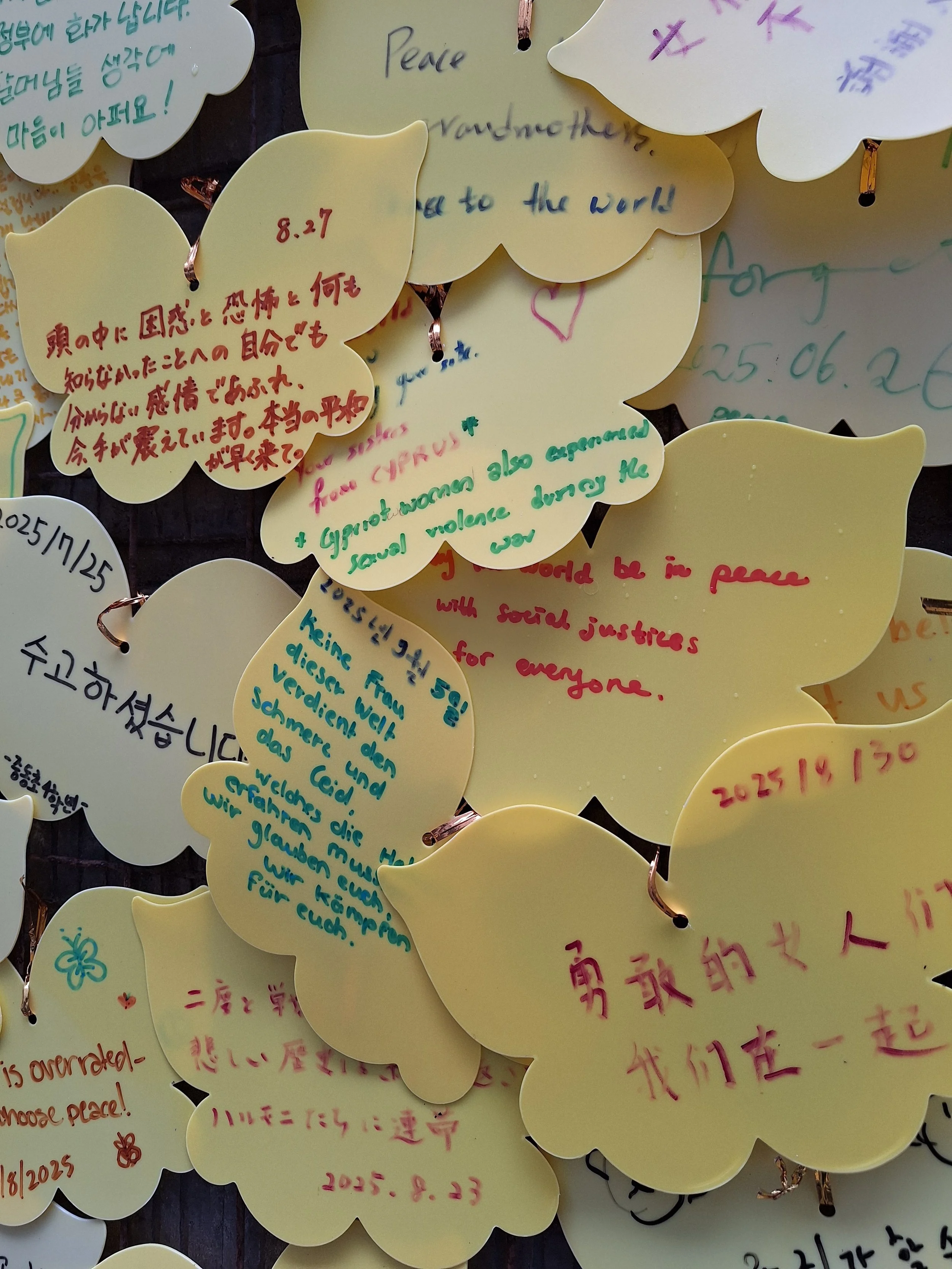

While travelling in Seoul on a rainy day, I walked uphill toward the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum. The street was quiet, unlike the crowded, spectacular tourist routes I had followed over the past few days. Following the paintings on the sides of the street, I arrived at a grey brick facade, covered with yellow butterfly notes bearing visitors’ messages of solidarity. Not monumental but intimate, the three-storey house unfolds a painful and long-silenced history of sexual slavery.

The visit raised questions which resurfaced a week later, when I visited another museum, the War Memorial of Korea. Whose history is being told here, and toward what vision of peace? How can hope, resilience and solidarity be cultivated while carrying historical trauma? Two museums, two memories. Both speak of war, violence and “peace”. Yet they imagine different moral worlds: one intimate, feminist, unsettling but reassuring; the other monumental, military, nationalist and masculine.

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum

As I opened the door, the small reception area was dark and quiet. A middle-aged woman behind the reception desk greeted me in Korean. Noticing my hesitation, she slowed her speech, shifting gently between Korean and English. When I told her I spoke “only a little Korean” as a foreigner, she smiled and replied gwaenchanh-ayo (it’s okay), patiently explaining the ticket price, audio guide and exhibition route. Then, she introduced the face printed on the ticket–the late Kim Bok-dong, one of the most prominent survivor-activists of Japanese military sexual slavery in WWII. She was referred to, alongside other victims, as halmoni (grandmother), a Korean kinship term with dignity and agency, instead of “comfort women”, a Japanese bureaucratic colonial category that reduced them to instruments of sexual exploitation in WWII.

The exhibition begins with a narrow gravel walkway that leads downwards. The crunch of stones underfoot, accompanied by the sound of gunfire, and the closeness of the walls create a bodily sense of confinement, ushering visitors into the halmonis’ suffering. Drawings made by survivors hang along the walls, guiding me deeper into the dimly lit basement where videos of the halmonis’ testimonies are played. In this dark, cramped space, I encountered the halmonis’ voices, their isolation and endurance and the heavy weight of history.

The next section opens into a brighter room displaying historical documents that reveal the scale and systematic organisation of Japanese military sexual slavery. It also traces the halmonis’ decades of activism: their struggle to break the silence, to demand accountability from the Japanese state, and to build solidarity in transnational movements against military sexual violence with those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Congo and elsewhere.

The Memorial Hall is the most saddening display. Names and dates of death on the bricks commemorate known victims. Victims whose names are unknown are also remembered, represented by black bricks. Hallam and Hockey (2001) argue that people manage relationships with the dead through materiality; memorials “deploy words in the service of a particular conception of memory and its relation to materiality” (171). Visitors do not encounter an abstract category of “comfort women”, but a tangible wall with names engraved that must be faced and walked along. Even for bricks without names, they give physical weight to the invisible deceased, bringing the “absent” present. According to the audio guide, despite its grief, the Memorial Hall is deliberately located at the brightest part of the museum, exposed to sunlight as a symbol of hope. As a site of ongoing relation, the hall makes the deceased halmonis visible and spatially orients the dead toward the living.

Hope also emerges from two special exhibitions, from the legacies of Kim Bok-Dong and the surprising solidarity between Korean halmonis and Vietnamese survivors of sexual violence committed by Korean soldiers during the Vietnam War. In the outdoor area below, the museum confronted a history rarely centred in South Korean public memory, featuring the testimonies of Vietnamese victims. Here, the familiar national narrative of Korea solely as a victim of colonial violence is unsettled. Koreans appear not only as those who were “wronged”, but also as those who “wronged” others.

The survivor-activist Kim Bok-dong said to Vietnamese survivors: “We are the same victims of Asian wars. The only difference is that they were harmed by the Korean military.” And another quote: “I am sorry, as a Korean citizen, that the Vietnamese suffered like us (halmonis) because of the Korean military. I will continue to support survivors of sexual violence around the world so that they may be consoled, even a little.”

The late Kim Bok-Dong’s lifetime dedication to peace, activism and women’s rights is inspiring, showing “victims” are not passive but resilient. For her, peace means a world where people “live comfortably without war”. She also extended her activism beyond South Korea’s national borders by establishing scholarships for ethnic Koreans in Japan, supporting Vietnamese survivors, and creating the Butterfly Fund to redirect Japanese government reparations to other survivors of wartime sexual violence worldwide.

The weekly Wednesday Demonstration in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul continues till today, demanding recognition and accountability. Activism seems like a long road; it is work, but it also works.

Before I left, I handed back the audio guide. The same reception woman asked gently, “Did you see everything well? Did you also visit the Vietnam section outside?” The exhibition’s heaviness lingered, but so did the warmth of the receptionist’s voice, Kim Bok-dong’s legacy and the hope cultivated by this space of memory and resilience.

As I left, I also left a butterfly note. These notes are a form of “memory writing”, a “hybrid” entanglement of “material objects” and “embodied practices” (Hallam & Jockey 2001: 177). The butterflies form a growing network of solidarity between halmonis, activists, other supporters, and those suffering abuses across the world. As each visitor leaves their note, they enter into a dialogical space that extends beyond the current time-space. The butterflies address both the living and the dead, and connect the past and future visitors.

A week later: the War Memorial of Korea

Again in the rain, I visited the War Memorial of Korea. I immediately felt the contrast between it and the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum. Where the feminist museum is only as big as a large house, this War Memorial has multiple indoor main halls and a large outdoor space with statues and flags. Its architecture is angular and grand.

Built to commemorate the Korean War and also in the hope of “peace”—but as in the “peaceful reunification of North and South Korea”—the War Memorial also serves as a pedagogical site for national military history. When I entered the museum, I encountered a group of young men in military uniform, who I believe were conscripts on a visit to learn about the military history and the Republic of Korea armed forces they were part of.

There is also a Memorial Hall. It honours soldiers and policemen killed in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Like the Memorial Hall in the War and Women’s Human Rights, it was quiet. The installations and sculptures titled “the Spirit of the Nation”, “Traces of Patriotism”, and the “Creation” represent the Republic of Korea, the desire for one non-separated nation, and hope despite past destructions. The deaths are sacrifices made for national unity.

The exhibitions display weaponry and war histories from the Three States era (from the 1st century BCE) to the present. The Korean War is framed through international alliance and sacrifice, emphasised as the United Nations’ first large-scale peacekeeping coalition, supported by 63 countries. Here, “peace” is defined through national security and collective military effort.

I specifically remember a gallery titled “From a Recipient Country to a Donor Nation.” It presents South Korean history as linear progress: from need to self-sufficiency, from being “helped” to becoming a “helper”. In its narration, with support from 63 countries, the Republic of Korea has risen from a war-torn aid recipient to a G20 economy and contributor to UN peacekeeping missions in places like South Sudan and Lebanon. I thought: isn’t this the teleology of modernity that anthropology so often critiques?

South Korea casts its past as “less developed,” only to reposition itself as a “modern” nation now able to assist the “Third World.” As anthropologists such as Wolf (1982) and Escobar (1995) critiqued, Eurocentric developmental narratives reproduce a single historical trajectory of progress that naturalises global hierarchies. Reinscribing this logic, South Korea adopts the very framework that once positioned it as lacking to advance itself geopolitically. As Cho Han (2000:59) notes, in South Korea, “after the 1970s, the discourse of nationalism was directly connected with economy-first policies that sought the development of a powerful nation.” Within this discourse, becoming a “donor” signals entry into modernity and geopolitical power. “Help” appears neutral and benevolent, while obscuring unequal power relations; “peace” emerges as the outcome of linear progress and geopolitical stability.

The Vietnam War is featured in the exhibition “Expeditionary Forces Room”, but only as a chapter highlighting the Republic of Korea's contributions to medical care and reconstruction. As expected, the dark history of sexual violence committed by Korean soldiers against the Vietnamese is absent. This museum, after all, is a patriotic space dedicated to honouring those who devoted their lives to the nation in wars from the past to the present, not a place for self-criticism. National guilt is not contained, tolerated or relieved by the space, but simply an elephant in the room, or perhaps the elephant is not even here.

Two narrations, different “sacrifices”

National museums reflect a form of politics that might be called sacrificial nationalism. The nation is imagined as something that must be sustained through the offering of lives. At the War Memorial of Korea, soldiers’ deaths are framed as meaningful sacrifices made for national survival, unity, and progress. Loss is not presented as tragic alone, but as necessary and honourable. Peace, here, is not the absence of violence but is achieved through disciplined bodies, military alliances, and a heroic willingness to die for the nation. The state presents military interventions, UN peacekeeping missions, and development aid as national generosity while obscuring whose labour, lives, and sufferings make these “sacrifices” and national glory possible.

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum exposes the exclusions built into this sacrificial nationalism. The halmonis’ suffering does not fit the heroic narrative of chosen sacrifice. Their bodies were not offered to protect the nation, but taken through imperial and militarised violence that rendered women’s lives expendable. This suffering is difficult to assimilate into nationalist memory because it disrupts the image of sacrifice as noble. By centring halmonis’ testimonies, sufferings and activism rather than heroic death, the museum does not convert gendered violence into a redemptive national story. Instead, it speaks of halmonis’ “sacrifices”—including victims who “sacrifice” their lives traumatically and survivors who “sacrifice” their time and effort in activism—as a political call to confront ongoing abuses of women’s human rights worldwide.

Offering a feminist critique, Cho Han (2000:57) argues that South Korea’s “compressed” economic growth produced “grand statepower and patriarchal families, but no citizens or autonomous individuals,” even as such “national persons” enabled the rapid growth. The halmonis sit uneasily within the nationalist discourse. Their activism can be absorbed into nationalism when it aligns with the discourse of anti-Japanese imperialism and helps cast South Korea, with its Butterfly Fund, as a global “helper” of other “Third World” women in need of “saving”. Yet, halmonis did more, especially with the inclusion of Vietnamese victims of Korean soldiers’ sexual violence, shattering the patriarchal nationalist discourse.

Two narrations, but both speak of “peace”

Both museums narrate the past of wars and imagine a future of peace. One centres on bodily abuses, trauma and sexual violence. The multisensory curation helps museum visitors step into the halmonis’ shoes (which is not to say the halmonis’ experience is translatable or anyone can simply “understand” or “feel” the same merely via an exhibition). Peace and hope emerge from feminist resistance and activism. The other centres on the nation, weaponry and military alliances, embedding peace within militarised security, state sovereignty and geopolitics.

Both speak of transnational solidarity; one through shared struggles against sexual violence, the other through multinational military cooperation. Both claim hope. Both speak the language of “peace”. Yet whose peace, and at what cost?

Can history be told without fixing permanent categories of victims and perpetrators? Solidarity is a step towards “peace”, but to avoid new exclusions, we have to be aware of who we are building solidarity with and not with. Perhaps peace is not a singular horizon but a contested moral project, shaping whose suffering counts and whose is rendered invisible.

It’s a long road to freedom and peace. And I have no answers. But I think to speak of peace, we must first ask: peace for whom, and narrated by whom? In museums and other educational spaces, this begins with listening differently, critically and attentively to silenced voices.

It’s raining, and it’ll rain again, but there is sunshine. The question is whether we can learn to see it through the shadows of rainclouds.

Bibliography

Cho Han, H.-J. 2000. ‘You are entrapped in an imaginary well’: the formation of subjectivity within compressed development - a feminist critique of modernity and Korean culture. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 1, 49–69.

Escobar, A. 1995. Encountering development: the making and unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Hallam, E. & J. Hockey 2001. Death, memory and material culture. Oxford: Berg.

Korea War-memorial Organization 2023. The War Memorial of Korea (available on-line: https://www.warmemo.or.kr:8443/Eng/index, accessed 8 February 2026).

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum 2024. The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum (available on-line: https://womenandwarmuseum.net/233, accessed 8 February 2026).

Wolf, E. 1982. Europe and the people without history. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

Whose Youth Pastor Has a Side Gig at Netflix?

The Stanford Prison Experiment, the Milgram Experiment, and Netflix reality TV. All equally crazed ventures that test the limits of the human psyche. From Love Is Blind to The Ultimatum, it would appear that there is a bored psychologist on the Netflix team who cares little for an ethical code. But I posit that this is not a dubious psychologist. This is a rogue youth pastor who seems intent on titillating the audience into chastity.

The Hays Code once barred directors from showing married couples sleeping in the same bed for fear that the very insinuation of sex would be too racy. On Temptation Island, a woman watches her fiancé have a threesome with two other women.

What do the depictions of love and lust on our television say about the dating world?

By S. J. Gul

“I would like a diamond ring on my wedding finger

I would like a big, shiny diamond

That I could wave around and talk and talk about it”

Every couple of months, it feels like Netflix drops a new bizarre dating show created by people who have never had sex, have simultaneously somehow been through five of the messiest divorces known to mankind, and yet possess a view of love solely informed by Disney movies. I feel like I’m being held hostage by a youth pastor who skimmed Deleuze in a coffee shop and went wild with it.

These shows tend to follow the same format: Contestants genuinely think they’re about to be on a raunchy dating show, only to be blindsided by a Foucauldian nightmare cone from “Factory, China”, silently surveilling the contestants throughout the villa as they are forced into a celibacy retreat. Maybe I just wanted to describe Too Hot to Handle, but the vast majority of these shows involve (a) the tiniest swimwear I’ve ever seen, (b) copious amounts of alcohol, and (c) explicit moral instruction as to what constitutes a good relationship (read: culminating in marriage, 2.5 children, and a designer pug).

And we love it! With several international spin-offs, we’ve encountered moments that have been seared into our skulls. From a contestant not knowing what language her own tattoo is in, fondly reminiscing about how a frat party where a girl broke her neck from falling off a roof, to not knowing where Australia is (this is all the same contestant, and only in the first episode at that - Haley, the woman you are).

In the age of situationships, dating app fatigue, and young people turning to matchmakers out of sheer exhaustion, the fantasy becomes obvious. Get out the stocks and your rotten produce! Let us punish the hot people for having meaningless drunk encounters with each other! Why can’t they want committed relationships with people like you?

The guy with the mullet may never want you back, and you can't punish him for letting you abandon your dignity by triple-texting him after 3 vodka crans - but the hot people on your TV can be forced to sit down together, finger-paint, and talk in circles about self-actualisation.

Some may argue that this is situated in a uniquely Western dilemma (particularly some incel with a Greek statue in their profile picture arguing that this is the outcome of Weimar Republic-level decadence and it’s all the fault of women having access to birth control). That reading falls apart the second you look at how so many versions of Love Is Blind exist, and my Arab father has provided me with his personal commentary on Love Is Blind, Habibi.

Sidenote: There is something painfully funny about the show presenting its concept as novel in a Middle Eastern context when so many Arab grandmothers also did not see how their husbands looked until the day they were married - and they didn't need a Netflix production team to do it.

The abject failure of shows like Indian Matchmaking and Jewish Matchmaking to actually make matches only illustrates this more clearly. Only one couple from the multiple seasons of Indian Matchmaking actually got married, with little contribution from the glorious Auntie Sima, and they divorced within a year amid reports of domestic violence (ET Online, 2023).

These shows lean into inflammatory narratives, inviting viewers to turn to their friends and say, “Why are women like that?” or “Ugh, men.” You get the unlikeable over-successful career women who are framed as too picky. You get men demanding supermodel wives while their hairlines sprint away from them at the speed of Sha’Carri Richardson.

I don’t mean to be overly frivolous here because there’s an interesting underlying tension between clashing ideals of compatibility. Some people treat a match as someone who mirrors them, someone with an impressive career wanting a peer who understands ambition. Others treat a match as someone who fills in the spots they leave blank. There isn’t really an explicit acknowledgement of this rather gendered expectation (women tend to want peerdom, men tend to want someone more complementary) - well, no acknowledgement beyond Sima Auntie telling every man, woman, and dog to lower their expectations and Aleeza of Jewish Matchmaking likewise instructing the singles to “date ‘em till you hate ‘em!”

In an era where so many people feel disillusioned about relationships, these shows give viewers the hope that there is something out there that transcends the often shallow interactions people have on dating apps. Someone could be surrounded by hot Instagram models and still be faithful to you. That they could fall in love before first sight.

And it also results in the sweet schadenfreude for cynics in seeing these comedically shallow relationships crumble and collapse. It provides a voyeuristic perspective of relationships that allows us to minimise our own worries by comparing them to someone else's. Your girlfriend may still be hung up on her ex-humiliationship, but at least she’s not having a threesome on Netflix after announcing her loyalty to you. It’s so bad out there, doesn't your mediocre partner, who never gets you flowers, look so much better in comparison?

While it is an open secret that repeat offenders like Harry Jowsey, who seem to be a permanent fixture on set, might not be falling in love like a Disney princess, this does not mean their emotions are fake. These shows project romance as a series of replicable steps and keywords shaped by the show’s incentives rather than as a private relationship. These shows reward accelerated intimacy and an unrealistic amount of emotional literacy. Imagine if you had to explain every move you made around your crush to a production crew for the cutaway to your confessional. Yet the feelings themselves can still be real. Under conditions of isolation, alcohol, and being deprived of distractions (on most sets, cast members don’t have access to their phones, books, or any other reprieve from what’s going on), emotions are heightened, making it possible to experience genuine vulnerability within an exaggerated romantic form. It may be disproportionate and slightly ridiculous, but it doesn’t mean it’s not real. In fact, acting slightly ridiculously is a well-known sign of being authentically in love.

While we may have never seen someone get stood up at the altar like in Love is Blind, we’ve all seen our friend (or been the friend!) whose boyfriend clearly doesn’t like them as much as they want him to.

In Chanté Joseph’s article, “Is Having a Boyfriend Embarassing?”, it argues that there's been an increasing cultural shift wherein women conceal the identities of their boyfriends (Joseph, 2025). A tacit acknowledgement that “boyfriend-land” is where individuality goes to die as you merge your identity with another person.

However, she highlights that while women may be concealing the identity of their boyfriends, they still post some form of soft launch - faces hiding between flowers or a strategic phone placement in a mirror selfie.

The cultural fixation can be summarised like so - people want to centre existing in a relationship but not necessarily their partners - the clout of having a socially approved relationship with the partner themselves being replaceable. Being in a relationship has benefits, but your partner is human and therefore has the capacity to be a liability that could embarrass you. In the words of renowned social theorist (Carpenter, Sabrina), "heartbreak is one thing, my ego's another".

When (not if) he does something humiliating, you can claim you were never that serious anyway. These Netflix shows have gamified this paranoia; every episode of Temptation Island is structured around "wait until you see what they did when you weren't watching." There's nothing more mortifying than having to archive old posts, scrubbing evidence of an ex. Your parents could just stop seeing each other; you must perform a digital murder of your own relationship while 400 people watch. Even so, you can never kill it completely - someone will screenshot your soft launch, and it's floating in a group chat you'll never see. Someone will ask about your ex at a party, and you’ll mentally draft a PR statement.

At first, I thought this was a result of a particularly curated social bubble. I wouldn’t be surprised by my friends’ conscious efforts to decenter romantic love. I am, however, an anthropology student with dyed hair, combat boots, and a tendency to wear pomegranate jewellery. My social circle is not representative of the cultural zeitgeist.

I think on the right, this situation is flipped in a mirror image. It's trad wife, not trad situationship! Forget meet-cutes in bookstores, and that ambiguous phase between friendship and romance that is both nostalgic and infuriating - Find Someone, Get Married, and Have A Socially Approved Relationship - in that order.

In both cases, it's decentering your individual partner from being a soulmate to being a placeholder romantic object. Both treat the actual human as interchangeable - what matters is the relationship as proof of concept.

This fixation makes sense in a world where stable jobs, affordable housing, and long-term security feel increasingly fictional. When material fairness collapses, romance becomes one of the last arenas where people still expect meritocracy. The bank may never approve of your loan to buy a too-small flat, but you don’t need a good credit score for your parents to approve of your future spouse.

No one owes you a living, but surely you are owed love! Specifically, a love made legible and “proven” through a piece of paper.

But even then, there’s been increasing cynicism.

While Netflix shows conveniently stop at the altar - with a total of 14 couples saying "I do" across the U.S. seasons of Love is Blind, and eight of those couples remain together as of late 2025, and an announced engagement on Perfect Match (which conveniently disintegrated after the premiere of the show).

I’ve recently been watching Couples Therapy on Showtime and in every comment section, you have at least one person praising the Gods that be, that they are single and not in a relationship like that. While the relationships pictured are ridiculously fraught, there’s something more authentic to them than the regular Netflix fare. The show regularly features middle-aged couples struggling to cope with finances, infidelity and trauma. It’s not as sexy; It’s still spectacle - with their beige background and therapist with a face that has subtitles. But there’s a glimpse of hope there; couples grappling with the roots of their issues stemming from childhood. It’s painfully earnest and sincere and therefore cringeworthy.

There’s a queer polyamorous couple engaging in a “conscious decoupling” that asks if they can send pictures of their cat when they are meant to not contact each other for two weeks.

There’s a couple who struggle with intimacy in an interreligious relationship because of an in-law repeatedly evoking demonic imagery to describe their relationship.

Of course, we don't want those relationships. We want a nice engagement and then a fade-to-black where everyone presumes we're living forever in the last five minutes of a rom-com.

I’m not saying that reality TV shows can exist as the frontier for showing us what dating should look like. But in a world where dating seems more fraught than ever for Gen Z, it’s interesting how the same shows provide different narratives: whether that’s inculcating puritanical abstinence until marriage, echoing the same message as most immigrant parents after you turn 25, “Don’t get a boyfriend, get a husband!” or encouraging a total divestment from relationships, accepting a certain heterofatalist mediocrity, maybe marriage has always sucked.

Maybe the real show isn’t on Netflix at all. It’s in the way we perform love for each other, for strangers, for algorithms, and for ourselves. We swipe, soft-launch and situationship our way into romantic risk aversion. We want a version of love where we can guarantee that the person you love will not hurt you because you will see the red flags a mile away. But a love that can be fully optimised is not intimacy. It is risk management. And until you find a consulting firm willing to take that on – and I give it 5 years till an LSE grad proposes just that – this does not make for marriage material.

But whatever it is, this isn’t your sign to redownload Hinge.

References

ET Online. (2023, August 23). Indian Matchmaking star Pradhyuman Maloo faces domestic violence allegations. The Economic Times; Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/new-updates/indian-matchmaking-star-pradhyuman-maloo-faces-domestic-violence-allegations/articleshow/102994179.cms?from=mdr

Joseph, C. (2025, October 29). Is Having a Boyfriend Embarrassing Now? Vogue. https://www.vogue.com/article/is-having-a-boyfriend-embarrassing-now

Doing One’s Part: An Anthropological Interrogation of Effective Altruism and Why We Help

Why do we help? It’s a question that has followed me from soup kitchens and homeless shelters to house-building sites. Here, I reflect on the uneasy space between care that feels meaningful and care that feels insufficient. Alongside this ethnographic texture, the essay turns to anthropology to sit with (and interrogate) the logic of Effective Altruism, a movement that urges us to measure, compare, and optimise our moral efforts. Without dismissing its importance, I ask what gets lost when value is reduced to what can be counted, and what remains when help is understood instead as presence, obligation, and the ordinary work of “doing one’s part” in a world that may never be fully repaired.

By Nadia Pritta Wibisono

There was cinnamon in the stew.

There was cinnamon in the air, too; dust suspended after it had been freshly ground from whole sticks, not the stale powdered kind kept in the back of the spice rack. The kitchen ran with a busy hum: people chopping vegetables with varying levels of confidence, someone wiping down a counter that would immediately be dirtied again, and I was dicing my second crate of pears for this evening’s crumble, observing it all while making small talk with a fellow dicer. The kitchen leader had his arms crossed as he looked at the whiteboard detailing today’s menu, which best utilised the donated ingredients in the kitchen.

The cinnamon felt almost excessive. It caught me off guard. Later, the volunteer in charge of the stew told me it was part of her family’s recipe. A small detail, offered without ceremony, folded into a meal that would be served to people who had nowhere else to be that evening.

London has more than 150 organisations working on homelessness. That number alone should tell you something. Not just about the scale of the problem, but about its stubbornness. The issue of homelessness is a dense, tangled knot of housing shortages, mental health crises, migration policy, labour precarity, addiction, austerity, and bureaucratic exhaustion. In policy circles, it’s often called a “wicked problem”—a term that manages to sound both technical and defeated.

Moving to London meant confronting the issue and visibility of homelessness every day. I started volunteering with a few organisations: soup kitchens, temporary shelters, and meal services. Sometimes it feels good in the way that helping often does, but sometimes it feels bleak. When I go home, feeling both satisfied and exhausted, the questions come:

Am I doing this because it helps, or because it helps me feel better about myself? Am I putting a band-aid on a gaping wound that requires surgery? Would my time be better spent elsewhere? Should I be doing something more aligned with my skills, or with causes that are said to have greater impact (and what does that even mean)?

I’ve been circling these questions for most of my life. When I was fifteen, I started my school’s first volunteer house-building project. After fundraising enough money for two houses, a handful of high school students spent a day under the blistering tropical heat at a construction site. We learnt to bend wires, mix and pour cement to build the foundation, which took hours and left a permanent scar still visible on my left arm. I remember watching the professional construction workers who taught us, finishing in hours what we struggled to approximate in a day. At the time, the logic seemed obvious to me: why would a group of teenagers do work that could be done faster, better, and definitely safer by trained construction workers instead? Wouldn’t it be more efficient for us to focus on fundraising and let the professionals do the job?

Years later, I learnt that this approach had a name: Effective Altruism. It has a simple premise: given limited resources, how can we do the most good? Effective Altruism draws on a utilitarian moral philosophy that leans heavily on evidence, measurement, and comparison. The appeal is obvious. Why wouldn’t we want to help out as many people as possible and make our efforts worthwhile? Effective Altruism resists vague goodness. It demands ROI-optimised rigour (Return of Investment), encourages impartiality, and urges us to care about suffering wherever it occurs, not just where it’s most visible or emotionally salient. It advocates for what they call “long-termism”, pushing us to zoom out of our human lifetimes and consider the generations yet to come.

Some of the causes championed by Effective Altruists are undeniably important. People inspired by Effective Altruism have referenced GiveWell’s research, for example, and donated to its recommended charities, such as the Against Malaria Foundation, which has distributed over 200 million insecticide-treated bednets. They reported that collectively, their efforts have “saved 159,000 lives”. Other priority causes they’ve calculated as important include AI safety, animal welfare, and pandemic prevention; causes we can all agree are important.

What about homelessness then?

If reducing suffering is the goal, then surely homelessness should be a priority. Living on the streets shortens lives. It damages health, dignity, and social belonging. It’s visible, immediate, and deeply human. And yet, within Effective Altruist frameworks, homelessness is not explicitly called a priority. The reasoning is usually framed in terms of cost-effectiveness. Homelessness is a complex, hard-to-evaluate social issue, and the same money spent elsewhere could do far more good. It’s altruism arbitrage: your £5 would go further in Lagos or La Paz than in London. So is working on homelessness, by Effective Altruist standards, ineffective?

___

I turn to anthropology to interrogate some of the principles of Effective Altruism.

I was drawn to Effective Altruism’s rigour to soothe myself from the frustration of seeing all the feel-good activism that treated beneficiaries as photo props. “Numbers don’t lie,” we always hear. The aura of neutral certainty appealed to me, but Sally Engle Merry (2011) argues that indicators conceal who gets to define them, use them, and for what purposes: “The deployment of statistical measures tends to replace political debate with technical expertise.” The numbers have names, and the numbers have faces.

Effective Altruism’s long-termism often carries an implicit faith in our ability to model the future: that with enough data, foresight, and analytical clarity, we can identify the right levers and pull them in time. In today’s short-termist world, thinking about the seven generations to come feels radical. In The Good Ancestor, Roman Krznaric shares the same long-termist belief, but introduces the notion of “deep-time humility”. Perhaps, by placing human history against the vast scale of deep time, it reminds us how provisional our knowledge really is, and how easily urgency can harden into certainty. Caring for the long-term is not only a question of choosing the right interventions, but of tempering confidence with restraint and avoiding “solutionism” as a default posture.

We are talking about value: what counts, and who gets to count it. David Graeber (2002) asked. He wrote about the “false coin” where market principles (rational, self-interested calculation) and their supposed opposites (family values, altruism, devotion) are presented as distinct but are, in fact, two sides of the same flawed system. Maybe I find Effective Altruism fascinating because, far from opposite sides of a coin, it welds market principles and altruism into one: a laminated moral economy rather than a coherent alloy.

Effective Altruism tends to treat value as something that can be abstracted from context, compared across causes, and optimised. Anthropology is more suspicious of such abstraction. Value, according to Graeber, “is the way actions become meaningful to the actors by being placed in some larger social whole, real or imagined’’. True value is deeply embedded in the social process itself, in the ongoing creation of human society, meaning, and relationships, rather than in detached, objectified, or individualistic notions perpetuated by dominant ideologies.

___

So then, why do we help?

The people I’ve met while volunteering aren’t naïve. They are clear-eyed about the limits of what they’re doing. Unlike Crisis UK’s “together we will end homelessness” slogan, none of the volunteers genuinely believes that they are going to end homelessness. Many of them regularly question whether their efforts matter, yet they do it anyway. Why?

A recurring conversation among volunteers is the paralysing moral overload of figuring out what to do when coming across a homeless person in the street. Sometimes buying a meal deal for someone sitting out in the cold or picking up a volunteering shift could be enough to make them feel like they have done their part, without fully addressing the issue.

“Survivor’s guilt” is a common phrase I hear. They say that life feels like the luck of the draw, that they were born lucky to be in a family that could afford school and housing, or lived in a city with a network of support.

“If I suddenly lose my job, I could just move back in with my parents. Relatives or even friends could give me some sort of support, but they don’t have anyone. The people back home, far, far away, are relying on them,” one volunteer shared.

Being born lucky also means they are mere inches from the chance of homelessness. “It’s like there is an invisible barrier separating the two worlds: the housed and the homeless,” someone brought up as we were chopping vegetables. The guilt is insurmountable: helping, penetrating that barrier, even when it never feels like enough, feels better than remaining paralysed by it.

___

Volunteering is also an act of reweaving the frayed social fabric of the city. In my conversation with a retired man who has volunteered at the shelter for eight years in a row, what initially seemed like a tangent gradually revealed something deeper.

“Developed places like London have become more affluent. The poor come up, ‘make it’, and forget about their past. Like my 86-year-old cousin Dot [who lives far away from the city], who has sons that don’t come back and help.” His voice slowed as he recalled these moments.

“I guess I was the same, too. When I was young, my aunty kept calling. I just left it to ring. What does that say about me? I regret not helping my aunty. She passed now…” He paused and looked into the distance.

“Maybe that’s why I volunteer.” Volunteering, for him, appeared to be a form of repentance, a way of being there for others now, in the face of earlier absences after moving to the city.

___

During meal service, we ladle stews into their bowls, give extra servings, and ask if they would like cream with their crumble. When it was time for us to close, I heard a group of patrons who seemed to have just met for the first time gather and call the volunteer leader to joke about giving “compliments to the chef” like they were in a fine dining establishment.

I asked why she continued to volunteer. She stated simply, “My country’s migration policies and border control have impacted the people we see today, and the people we probably would never see. Doing this is my duty as a British citizen to make up for it. I’m just doing my part.”

She then loaded the van with empty gastros to return to the kitchen, not to rest, but to prepare for the next day.

___

These motivations look messy from an optimisation standpoint. They are inconsistent. They are emotional. They are deeply personal. And yet, they are not trivial. They reflect an understanding of ethics not as a problem to be solved once and for all, but as something lived, negotiated, and revisited over time.

Anthropologists like Veena Das and Michael Lambek (2010) sometimes refer to this as ordinary ethics: the ways people make moral judgements in the course of everyday life, without grand theories or guarantees. Ordinary ethics doesn’t promise maximum impact. It doesn’t pretend to be pure. It operates in conditions of uncertainty and constraint. It accepts that moral life often involves doing what one can, rather than what would be ideal.

This doesn’t mean abandoning effectiveness. It means recognising that not all forms of value are legible at scale. Care, especially relational care, does not always aggregate neatly. Its effects are diffuse. They show up in moments of recognition, in the maintenance of dignity, in the quiet refusal to let someone be reduced to a problem to be managed.

There is a tendency, in debates about helping, to frame things as either/or. Either you care about effectiveness, or you indulge in feel-good gestures. Either you think globally, or you’re trapped in parochial concern. But these binaries flatten moral life. They obscure the fact that different value systems can coexist, sometimes uneasily, without one invalidating the other.

Effective Altruism has pushed important conversations forward. It has forced many of us to confront the limits of intuition and the dangers of sentimentalism. But anthropology reminds us that value is not only about outcomes. It is also about relationships. About presence. About the quiet insistence that care still belongs here—sometimes no more elaborate than cinnamon in a pot of stew.

References

Crisis. (2019). Ending homelessness: Together we will end homelessness. Crisis. https://www.crisis.org.uk/ending-homelessness/

Das, V. (2012). Ordinary Ethics. A Companion to Moral Anthropology, 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118290620.ch8

Effective Altruism. (2022). Introduction to Effective Altruism | Effective Altruism. Effective Altruism. https://www.effectivealtruism.org/articles/introduction-to-effective-altruism

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward An Anthropological Theory of Value. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780312299064

Homeless Link. (2023). 2023 London Atlas of Homelessness Services Launched. Homeless Link. https://homeless.org.uk/news/2023-london-atlas-of-homelessness-services-launched/

Krznaric, R. (2020). The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World. Wh Allen, Penguin Random House.

Lambek, M. (2010). Ordinary Ethics: Anthropology, Language, and Action. Fordham University Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt13x07p9

Merry, S. E. (2011). Measuring the World: Indicators, Human Rights, and Global Governance. Current Anthropology, 52(S3), S83–S95. https://doi.org/10.1086/657241

The Palestinian “Disaster” Image

Palestinian photographers who document suffering under occupation face an ethical paradox that collapses the distance between photographer and subject. Through the case of photojournalist Ashraf Amra's refusal to photograph the 2015 Dawabsheh family funeral, the analysis argues that the ethics of imaging suffering under occupation is about navigating an impossible position where both visibility and invisibility serve structures of colonial violence. The work demonstrates how digital proliferation produces "accountability theater," reframing the ethics of disaster photography from questions of representation to questions of reception.

By Leen Jumah

When the photograph of four-year-old Ali Dawabsheh's charred bedroom went viral in 2015, Palestinian photojournalist Ashraf Amra faced an impossible choice: document the scene where an entire family burned alive in a fatal settler attack, or protect the dignity of the dead. He took the photograph. Three days later, his editor asked him to return and photograph the funeral. This time, he refused.

Palestinian photographers have become the world's most prolific documentarians of their own suffering – and the most conflicted about it. In Gaza alone, over 200 journalists hold press cards. American critic Susan Sontag argued that photographs of disaster risk immunize viewers through overexposure, transforming atrocity into an aesthetic object. But what happens when the photographers and the photographed are the same people? When the camera is not a colonial instrument wielded by outsiders, but a tool of Palestinian self-representation under occupation?

During the ever-digital age, it's difficult to understand where to draw the line, especially when all aspects of the genocide are being shared online, from Gaza daily routine videos to "what I eat in a day war edition." Is it Palestinian photographers' responsibility to photograph images of wailing mothers and share them? Is it really holding anyone accountable if there are tens of thousands of the same familiar cries of mothers and fathers at their children's graves? Does visibility equal accountability when the images are endless? Palestinian photographers reveal what Sontag could not fully articulate: the ethics of imaging suffering under occupation is not about choosing between dignity and documentation, but about navigating an impossible position where both visibility and invisibility serve structures of colonial violence.

Sontag's "Regarding the Pain of Others" (2003) warns that photographic documentation of atrocity produces a peculiar kind of spectatorship, one that simultaneously acknowledges suffering and maintains a comfortable distance from it. She describes how images of distant wars become consumable, how repeated exposure breeds a dangerous familiarity that mistakes recognition for understanding. The photograph becomes what she calls "a means of making 'real' matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore." Yet Sontag's analysis assumes a fundamental separation between the photographer and the subject, between those who document and those who suffer. Palestinian image-making collapses this distance entirely.

American Anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod (2025) extends this critique by examining how cultural representation under conditions of domination creates the "pornography of pain", images that simultaneously expose suffering and reproduce the power dynamics that enable it. When privileged audiences consume images of Palestinian death, they often position Palestinians as perpetual victims, as people who only exist in relation to their suffering. Abu-Lughod argues that even well-intentioned documentation can reinforce colonial narratives when the viewer's gaze remains unchanged, when the image confirms rather than challenges preexisting assumptions about who deserves sympathy and who deserves sovereignty.

The Palestinian photographer exists within this paradox. To not photograph is to allow atrocity to occur without witness, to grant permission for the erasure that occupation depends upon. Israel's systematic targeting of Palestinian journalists reveals how threatening Palestinian self-documentation is to the occupation's narrative control. Yet to photograph is to participate in an economy of images where Palestinian humanity is only legible through death, where the price of visibility is the reduction of an entire people to their most traumatic moments.

Amra's refusal to photograph Ali Dawabsheh's funeral represents not abandonment but recognition of this impossible bind. Having documented the crime scene, having created evidence of the attack, he drew a line at transforming private grief into a public spectacle. His refusal acknowledges what the endless stream of images obscures: there is a difference between documentation as evidence and documentation as performance, between making atrocity visible and making it consumable.

The digital age has intensified this dilemma exponentially. Social media platforms have transformed Palestinian photographers into involuntary content creators, their documentation immediately absorbed into algorithmic feeds where images of children's bodies appear between Netflix Ads and bikini pics. The "what I eat in a day" videos from Gaza emerge from this impossible context as an attempt to assert normalcy, to claim humanity beyond suffering, yet inevitably framed by the siege conditions that make a simple meal an act of survival worth documenting.

This proliferation creates what I might like to call “accountability theater”. When a mother's wail becomes one among thousands, when each new massacre produces the same outcry followed by the same inaction, the image loses its capacity to shock precisely because it has succeeded in becoming visible. The problem is not, as Sontag feared, that viewers become numb to distant suffering. The problem is that visibility without consequences is its own form of violence, it forces Palestinians to perform their grief endlessly while offering no transformation of the conditions that produce it.

Abu-Lughod's framework helps explain why this visibility fails. The pornography of pain operates by offering viewers the pleasurable sensation of moral righteousness through sympathy without demanding any structural change. The viewer can feel moved, can even feel outraged, while maintaining the distance that allows occupation to continue.

The image becomes a substitute for action, proof that "something is being done" simply because "something is being seen."

Palestinian photographers understand this trap intimately. They know their images will be consumed by audiences who treat Palestinian death as inevitable, as the tragic but unchangeable backdrop of Middle Eastern politics. They know their documentation will be used selectively, that images of Palestinian suffering circulate freely while images of Palestinian resistance are labeled as terrorist propaganda. They know that no matter how many children they photograph, the phrase "Israel has a right to defend itself" will follow each massacre like punctuation. Yet they continue photographing. Not because they believe visibility alone will end occupation, but because invisibility guarantees its continuation. The choice is not between dignity and documentation, but between different forms of violation. To refuse to photograph is to allow the occupation's preferred narrative of empty lands and absent people. To photograph is to create an archive that refuses erasure even when it cannot yet force accountability.

This is the ethics of imaging under occupation: there are no good choices, only choices made under duress. Amra's photographs of the Dawabsheh home serve as evidence in a legal system that has yet to deliver justice, but they exist nonetheless. They wait, as Palestinian photographers wait, for a future where Palestinian testimony is valued and translates into transformation rather than recognition. The question is not whether Palestinian photographers should stop documenting their reality because they cannot afford to. The question is what responsibilities viewers bear when confronted with this documentation. Sontag and Abu-Lughod both understood that the problem lies not in the image itself but in the structures of power that determine how images are received, interpreted, and acted upon. Until those structures change, Palestinian photographers will continue navigating the impossible space between dignity and documentation, creating an archive of atrocity that demands not just to be seen, but to be answered.

References:

Abu-Lughod, L. (2025). “Revisiting the Awkward Relationship of Feminism and Anthropology” [Lecture]. The Juliet Mitchell Lecture, Cambridge University Corpus Christi College. 15 October.

Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador.

Can sensory ethnography redistribute authority?

This commentary essay asks whether sensory ethnography can truly redistribute authority, and if not, where its failure occurs. Drawing on debates around sensory methods, participatory pedagogy, and (un)marked authorship, I provide a reflexive account of my own mini-ethnographic experiment. Through this, I suggest that reclaiming the ‘I’ is not a confessional gesture but a methodological stance to resist the fantasy of neutral observation.

By Junghee Yang

One of the enduring attractions and challenges of ethnography lies in the demand to translate corporeal, embodied experience into language. This process entails two interrelated dilemmas: on the one hand, attempts to attend to non-verbal cues of smell, touch, sound, and affect are inevitably reduced into language, flattening precisely what makes them meaningful; on the other, this reliance on textualisation reveals broader questions of authority, neutrality, and the politics of who can write from where. These acute dilemmas emerged during my own mini-ethnography project on sensory experiences and emotional labour in shared kitchens of student residential halls. I found myself continuously hovering between erasure of my bodily presence in the name of analytical distance and the risk of over-marking it as experiential authority, until I settled to confront the need for vulnerability and partiality.

During fieldwork, the role of the observer prioritises visual metaphors, potentially overlooking other modes of knowing (touching, smelling, listening, moving, and feeling). I found this especially true in my own field site, where sensory cues like smell and sound often revealed more about social dynamics than visual observation alone. Scholars like Sarah Pink propose sensory ethnography as a remedy. In “Doing Sensory Ethnography” (2009), Pink critiques the visual/textual bias of ethnography and advocates for “participant sensing,” which emphasises marginalised senses. Rather than about diversifying data, it is about facilitating relational interactions between researcher and participant. By “walking with others” or just by “being there,” the ethnographer learns as an apprentice and gains access to otherwise unrecognised forms of knowledge (22).

Initially, I drew on Pink (2009)’s concept of sensory ethnography as a form of apprenticeship, expecting this approach would help me make sense of multisensory experience into a more generalised form of knowledge. However, the writing process revealed that sensory data was always filtered by my body, my positionality, and my habits of perception. As a Korean woman interacting mostly with Asian women from India and China, my sense of what counted as ‘foreign’, ‘familiar’, or ‘Western’, and even what counted as sensory data in the first place, was already shaped. Although I intentionally included European and male participants to diversify perspectives, I noticed myself unconsciously aligning with the former through gender and with the latter through cultural familiarity. I was continuously aligning and distancing between the insider and outsider positions depending on the relational context, closely reflecting what Narayan (1993) calls a “multiplex identity” (673).

What seems like a matter of identity and proximity in the field becomes a question of authority on the page. As Atkinson and Hammersley (1994) famously critiqued, anthropology’s longstanding overemphasis on textual forms, reinforced by the broader ‘rhetorical turn’ in the social sciences, has constrained the possibilities of ethnographic insight. Before entering the field, researchers consume canonical, standard texts that shape how they expect the field to appear; after fieldwork, they produce similarly structured narratives that contribute to what Geertz (1973) described as a “literary convention.” In it, ways of seeing and knowing are standardised as a genre of textual product. Their critique still rings true as an invitation to reflect on the aesthetics and ethics of ethnographic texts, rather than a call to abandon writing.

Interpreting this critique as a call to expand ethnographic tools to photography, film, or other visual media would miss the point. What Atkinson and Hammersley point to is a more complex dilemma in the anthropological practices of reading our inter-textual world, both literally and figuratively. In the literal or usual sense, ‘text’ refers to techniques of ethnographic writing that have historically privileged visual information and language-reliant knowledge production. In the figurative sense, ‘text’ stands for the cultural baggage and power relations that shape the production and consumption of ethnography. In this context, the risk is not simply an overreliance on writing or vision, but a narrowing of what observation is allowed to register. When seeing becomes the dominant mode of knowing, ethnographers risk, ironically, losing sight of other forms of presence. In practice, these losses (embodied non-verbal senses, ethical and political accountability) are inseparably intertwined. This raises a question that sensory ethnography aims to answer: If sensory ethnography enables new ways of seeing and listening, can it also redistribute authority?

My proximity to the field also created a set of difficulties during the participant observation and the writing process that followed. I struggled to leave a void in the data, filling in narrative gaps with my own voice, not in the analytical sense, but in the generative sense. At the same time, I hesitated to quote myself, worrying that these would make the project appear too personal, particularly given that my field site included my living space, and my research access came so easily compared to peers’ projects. This hesitation persisted even though I was aware that my sensory impressions constituted a central source of field knowledge.

I also struggled with using the first-person voice, fearing it would appear messy or insufficiently theoretical. To compensate, I conducted more interviews, anticipating that expanding the number of external voices might legitimise the text where my own presence felt excessive. Only later in the writing process did I recognise how this impulse mirrored a pursuit of ‘professionalism’ and a broader disciplinary challenge. Revising the project meant not resolving this tension, but letting it remain visible. It also exposes the myth of ‘complete participation’: in my case, insiders perform distance in the hope of meeting academic expectations. Further, it exposes an irony of sensory ethnography where writers could minimise their own body, filtering out their interpretation of smell and sound, although the sensory research requires embodied honesty. These realisations led to revisions in both content and form. I rewrote a significant portion of my mini ethnography from the third-person description with a first-person narrative of my own sensory experience. This felt like a bold move, to expose ‘I’ as both asset and liability.

Here, I realised Pink’s suggestion maintains a methodological invention rather than a political one. Without sensitive attention to positionality and power, sensory methods risk becoming another form of extraction or Othering. There remains the risk of reproducing an extractive gaze that simply collects sensory data without interrogating its own authority, even when the fieldwork appears immersive. I call this the ‘Sniffing Coloniser’: a figure who claims closeness through embodied experience yet reinforces hierarchies by narrating sensory difference. Atkinson (2014) similarly critiques this possibility of sensory ethnography becoming performative, suggesting that researchers may ‘do’ sensory work to appear progressive while unchallenging institutional norms (79). Then the more pressing question becomes: When sensory ethnography fails to redistribute authority, where does that failure occur?

Arjun Shankar’s (2019) concept of “participatory pedagogy” offers a useful response. Drawing on fieldwork and a participatory photography project with youths in rural India, Shankar experiments with transgressing sensory biases to learn how images can be heard. Shankar’s pedagogy of listening, or “participatory hearing”, is grounded in reciprocal teaching and learning in the field, which enables the participants’ “practices of refusal” (231) on dominant narratives about rural life. By taking these refusals seriously, the researcher is forced to begin from narratives of lack and powerlessness, rather than omniscience. Consequently, Shankar models a humbler anthropology that foregrounds co-creation, reciprocity, and refusal as methodological commitments. Rather than resolving questions of authority, this approach reframes how authority might be unsettled through practices of listening.

Shankar’s intervention makes newly visible another enduring dilemma in anthropology: the tension between claims to neutrality and the politics of marked and unmarked authorship. This is not a failure of participatory pedagogy per se. Rather, it reveals a constraint imposed when such experiments must ultimately take the form of a readable academic text. As Atkinson and Hammersley (1994) already observed, while science and rhetoric cannot be sharply distinguished in ethnographic writing, the dominant style still favours authorial omniscience. This compels researchers to position themselves as neutral, objective observers distinguishable from the Other. In this form, ethnographic writing is not merely a genre but a persuasive apparatus that translates qualitative experience into scientific knowledge and secures anthropology’s disciplinary authority—an apparatus shared, in different ways, across research traditions beyond anthropology. The move toward humbler, sensory ethnographies often faces requirements of renewed distancing at the moment these experiences are rendered as data, inscribing the familiar divide between the Author and the Other. As “Writing Culture” (Clifford and Marcus 1986) reminds us, this is not a stylistic issue but an ethical and political one.

Put differently, participatory pedagogy is not a remedy if thick description continues to involve others on unequal terms. Crucially, this tension extends beyond anthropology. Feminist geographer Max Liboiron (2021) critiques similar dynamics in the academic norm of unmarked whiteness:

It is common to introduce Indigenous authors with their nation/affiliation, while settler and white scholars almost always remain unmarked, like “Lloyd Stouffer.” This unmarking is one act among many that recentres settlers and whiteness as an unexceptional norm, while deviations have to be marked and named. Simone de Beauvoir (French) called this positionality both “positive and neutral, as is indicated by the common use of man to designate human beings in general.” (3).

Un/marking is about the power that decides who gets to speak as a universal voice and who must speak from a situated voice. Some researchers, such as Sophie Chao, insist on full transparency, opening their works with positional declarations: “I write this commentary from the positionality of a Sino-French female, middle-class scholar, trained in Anglo-European forms of research and operating within a discipline – anthropology […]” (Lundberg, Regis, et al. 5). Her model shows how reflexivity rather than composed objectivity exposes the politics of knowledge production, marking and rendering the researcher’s positionality thick rather than neutral.

The value of such experiments lies in their capacity to expose how sensory descriptions can be shaped by culturally situated or class-specific habits of perception. What becomes legible as ‘foreign’, ‘familiar’ or even as sensory data is already subjectively distributed across bodies, backgrounds, and social proximities, which is a point that became unavoidable through my own mini-ethnography. Again, in exploring the (inter)textual world of contemporary anthropology, methodological and political dimensions of text and observation cannot be seen as separate domains.

Sensory ethnography attempts richer ways of seeing and listening, but my experience suggests that its political stakes do not lie in how many senses we activate, or how immersive our fieldwork appears. They lie in a quieter, more uncomfortable moment, predominantly after the fieldwork: when sensory experiences become text, and when the writer decides what to do with the ‘I’. When sensory ethnography fails to redistribute authority, the failure happens here. When embodied knowledge is translated into a readable form that argues neutrality, fluency, or professionalism at the cost of the writer’s marked position. Reclaiming the ‘I’ in sensory ethnography is not about self-disclosure of authenticity, nor is it a confessional tool. It is about refusing the fantasy of neutral observation and staying with the risks of writing from somewhere.

Bibliography

Atkinson, Paul. For Ethnography. SAGE, 2014.

Atkinson, Paul, and Martyn Hammersley. “Ethnography and Participant Observation.” Handbook of Qualitative Research, Sage, 1994.

Clifford, James, and George E Marcus. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. University Of California Press, 1986.

Liboiron, Max. Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press, 2021.

Lundberg, Anita, et al. “Decolonizing the Tropics: Part One.” ETropic: Electronic Journal of Studies in the Tropics, vol. 22, no. 1, James Cook University, July 2023, pp. 1–28, https://doi.org/10.25120/etropic.22.1.2023.3998. Accessed 2 Oct. 2023.

Narayan, Kirin. “How Native Is a ‘Native’ Anthropologist?” American Anthropologist, vol. 95, no. 3, Sept. 1993, pp. 671–86, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1993.95.3.02a00070.

Pink, Sarah. “Doing Sensory Ethnography.” Sage Research Methods, vol. 1, no. 1, 2009, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249383.

Shankar, Arjun. “Listening to Images, Participatory Pedagogy, and Anthropological (Re‐)Inventions.” American Anthropologist, vol. 121, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 229–42, https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13205. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

Why don’t more anthropologists work in pairs in the field?

Why does anthropology continue to valorise the lone ethnographer? This piece explores the enduring romanticisation of solo fieldwork and criticises the epistemological individualism that positions the solitary researcher as the authoritative interpreter of cultural knowledge.

By Tin Sum Ying

In 1967, Renato and Michelle Rosaldo travelled to the Philippines to conduct fieldwork on the Ilongot people of northern Luzon, investigating the history of local headhunting practices – a form of ritualised killing involving the taking of a victim’s head as a trophy. In trying to comprehend why men beheaded their enemies, Renato found insight in the idea of releasing liget, which Ilongot described as the feeling of intense rage experienced in bereavement. As he reflected, he initially struggled to grasp the concept of liget on an embodied level before experiencing a devastating loss of his own, which enabled him to identify with headhunting as a way to assert agency in the face of senseless tragedy (Rosaldo, 1993). In contrast, Shelly interpreted headhunting as an activity to allow young men to assert themselves in Ilongot society and achieve a ‘completed’ adult status, framing it as a “form of generativity that is both social and concrete […] born in a youth’s desire to equal peers and reach their elders” (Rosaldo, 1980). These two interpretations invoked different theoretical traditions – one personal, subjective and self-analytical, the other focused on the social functions of status and prestige – yet which approach was more correct? Or is there value in holding both simultaneously?

Two anthropologists, two perspectives, one fieldsite; and yet this kind of dual fieldwork remains rare. Anthropological inquiry has long been built on the ideal of the solitary ethnographer, the privileged, isolated researcher who embeds themselves into a social context and emerges as an authoritative expert. Even as Malinowski established participant observation as the foundational model of anthropological enquiry, critiquing earlier ‘armchair anthropologists’ who theorised about distant cultures without direct engagement, he nonetheless took for granted their individualist approach to research. In the Malinowskian paradigm, a single ethnographer would enter the field with a bag of methodological and theoretical tricks to transform people’s narratives, experiences, performances and intimacies into a piece of research; this scientific approach to grasping the native’s point of view expects interlocutors to ‘open up’ and articulate their worldviews, beliefs and practices to the anthropologist, who assumes the role of the authority who validates, analyses and gives meaning to their confessions. As Rosaldo critiques, “The Sacred Bundle the Lone Ethnographer handed his successors includes a complicity with imperialism, a commitment to objectivism, and a belief in monumentalism […] and a strict division of labour between the ‘detached’ ethnographer and ‘his native’” (Rosaldo, 1993). In this paradigm, ‘anthropological knowledge’ is situated within a framework of control, where explanation and articulation form mechanisms of power.

Yet even as anthropology has moved away from an unquestioning adherence to naïve realism, recognising the arrogance implied in the ethnographer’s assumed authority to “explain the other”, the persistent reliance on individual research reflects a continued romanticisation of the ‘lone ethnographer’ figure. While the postmodern crisis of representation forced anthropologists to acknowledge that ethnographic research involves constructing partial, situated truths rather than uncovering an ‘objective reality’ (Clifford and Marcus, 1986), there remains a sense that the discipline’s critical turn is enmeshed in the same power dynamics it critiques. An idealisation of epistemological individualism means that the modern anthropologist risks being trapped in a form of ‘hyper-reflexivity’ that emphasises the externalisation of positionalities, identities and desires, reflecting on how they might affect research without offering truly counterbalancing perspectives. In the era of self-scrutiny and confession, the ethnographic encounter becomes a mere performance of self-awareness. It is perhaps ironic that while anthropology has long aimed to critique and challenge Western intellectual traditions, it nevertheless upholds the myth of the fieldworker as “maverick and individualist”(Sanjeck, 1990), glorifying novelty and individual brilliance while dismissing collaboration and pathologising overlapping research interests.

And ethical critiques aside, while ethnographic individualism and subjectivity should be valorised for fostering the rich, personalised insights crucial to anthropological knowledge-making, they also introduce pragmatic issues regarding accountability, rigour and transparency. It is near-impossible to externally verify all aspects of conducted research – even with supervisor oversight – particularly as ethical procedures require falsifying the names and details of key settings and interlocutors (as seen in the controversy around works like Alice Goffman’s On the Run). Again, the system depends on trust and the privileged position of the single anthropologist for generating truth.

What possibilities could arise if we abandoned the lone ethnographer model? To propose a thought experiment, I imagine embedding two semi-independent researchers in the same fieldsite, not to validate each other’s findings but to intentionally observe and cultivate different approaches. This is not quite the same as the practice of a second anthropologist revisiting a site of past research, such as Kathleen Gough’s re-analysis of The Nuer, though of course such analyses play a crucial role in situating and updating anthropology within ongoing discourse. As I conceive it, a ‘parallel’ approach would begin with some shared research interests and questions but subsequently allow researchers the freedom to pursue divergent trajectories, where the aim would not be to reinforce a single interpretation of ‘truth’ but to explore how different perspectives might evolve in contrast. This would make explicit anthropology’s constructed nature, highlighting that subjective and partial knowledge is a key feature – and strength – of the discipline. Given that ethnography deliberately refuses preconceived hypotheses, such an approach would foreground how meaning is shaped by the confluence of what interlocutors and individual academics find significant in the field.

A parallel approach would also serve as a ‘counterfactual case’, shifting reflexivity from a mere intellectual acknowledgement of biases to something tangible and relational. By embracing epistemological multiplicity and discursive thought, we could simultaneously engage explicitly with positionality while increasing trust and lowering the risk of falsification. And beyond the methodological implications, this model could potentially inspire innovative forms of ethnographic writing, where juxtaposed accounts could highlight contradictions and real-time debates between researchers. Rather than ‘collaboration’ in the conventional sense, a ‘dialogue of divergence’ would stress the conflicts and unresolved tensions inherent in interpretation, raising the question of, what if the ideas we produce are irreconcilable? (and isn’t that exciting)?

Of course, this approach does not dissolve the hierarchies between anthropologists and interlocutors but instead keeps the anthropologist-as-interpreter structure intact. Yet I hold that such internal contestation introduces a different kind of destabilisation, one that directly challenges the solitary anthropologist’s epistemological authority and forces us to confess that ‘ethnographic truth’ is multiple. Rather than curating an “opacity”, which, to me, continues to privilege the anthropologist as the arbiter of what is revealed and concealed, embracing partiality and productive unknowability could generate a kind of radical transparency.

If this proposal is theoretically vague, that is because I am not entirely convinced that it could work in practice. Anthropological partnerships, where they do occur, often emerge for deeply personal reasons (most commonly because the researchers are married, given the extended amounts of time spent in the field); purposefully maintaining a working partnership in the field might be more challenging. Introducing a second semi-independent fieldworker would also introduce additional complexities, not least the issue of ‘funding overlap’ in an ideological system that prioritises originality as the key measure of the value of knowledge. There is also the question of authorship: how would researchers account for their partner’s contributions in a framework of intellectual property that fails to accommodate the inherently social and fluid nature of knowledge production?

And that is not to say there are no methodological benefits to solitude. Instead of reinforcing power dynamics, working alone can be a way of cultivating vulnerability – as successful research is contingent on the generosity, hospitality and emotional investment of interlocutors, a solo ethnographer may enable deeper engagement precisely by appearing more approachable and ‘in need of care’. The introduction of a second ethnographer could disrupt this, potentially reinforcing a sense of distance or self-sufficiency. But this, too, could be worth investigating; studying how the presence of multiple researchers shapes the field itself could offer valuable insight into the relational nature of ethnographic immersion.

I can’t claim to have any definitive answers – I am simply proposing a thought experiment, one which I hope is exciting and enriching to think about. As opposed to simply assuming that ‘two perspectives are better than one’, this could be a stimulating way of experimenting with partial truths, immersion and vulnerability, and a method of externalising core theoretical debates. Perhaps the real question isn’t why don’t anthropologists work in pairs? but rather, why do we still valorise the individual ethnographic gaze in a discipline that claims to embrace multiplicity and polyvocality?

Note to actual anthropologists – if you’re reading this, please let me know where I’m wrong (in particular, I have no idea how collaboration between anthropologists and research assistants actually works)! I fully acknowledge that it’s a bit presumptuous for me to write this as a second-year anthropology student with no fieldwork experience, so I would be very grateful to hear any insights and critiques.

Bibliography:

Clifford, J. and Marcus, G.E. (1986). Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley, Calif. ; London: University Of California Press.

Rosaldo, M.Z. (1980). Knowledge and passion : Ilongot notions of self and social life. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Rosaldo, R. (2014). Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage. The Day of Shelly’s Death, pp.117–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822376736-003.

Sanjek, R. (1990). Fieldnotes : the Makings of Anthropology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

In Conversation with Neil Armstrong